Movie Guru Rating:

Comment

on this review

| |

The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg recalls a Jewish giant and national hero

by Jesse Fox Mayshark

I come from maybe the last generation of American boys to grow up thinking that, as far as sports were concerned, there was baseball and then there was everything else. I followed my teams (the Red Sox and, paradoxically, the Yankees) fervently, read box scores and collected autographs (all of them subsequently lost except for my prized, faded Nolan Ryan and Vida Blue cards).

I also loved the game's stories, its history and legends and myths. I knew about the "shot heard round the world" that catapulted the Giants into the 1951 World Series, and Don Larsen's perfect game, and Ted Williams batting .400, and DiMaggio's hitting streak. I read a whole book about Roger Maris. But somewhere in there, I missed Hank Greenberg. Not completely—I knew his name, I had a replica vintage card with his photo and statistics on it—but I lumped him in with a lot of other golden age greats, classic hitters like Jimmie Foxx and Honus Wagner and Babe Herman.

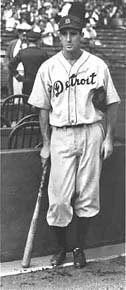

Watching the entertaining, insightful, and genuinely moving documentary The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg—the centerpiece of this weekend's Knoxville Jewish Film Festival—I realized that my oversight was largely because of my ethnic blind spots. Not only was I not Jewish, but I was in my teens before it really occurred to me that being Jewish meant something in particular. The name Greenberg itself wouldn't have signified anything more to me than Brown or Johnson or Smith. But as Aviva Kempner's film shows, for several generations of American Jews and gentiles alike, Hank Greenberg was a one-man watershed. With his towering strength and gentle, slightly worried smile, he almost single-handedly secured Jews a place in the American mainstream.

Greenberg, who played for the Detroit Tigers during most of the 1930s and '40s (apart from a four-year military stint during World War II), was not the first Jewish ballplayer. But he was the first to be a superstar, and one of the first to proudly claim his heritage. Many before him changed their names to avoid discrimination. When Greenberg had to decide whether or not to play on Rosh Hashanah in the midst of a heated pennant race, the entire city of Detroit waited on his choice. When he went ahead and suited up (with his rabbi's blessing) and won the game with a 10th-inning home run, the Detroit Free Press printed "Happy New Year" in Hebrew on its front page. Likewise, when he chose to sit out on Yom Kippur, he was saluted for his dedication to his faith.

Kempner tells the story through a diverse selection of interviews with Greenberg's old teammates, fans, sportswriters, and family members, as well as archival reminiscenses from the man himself (he died in the 1980s). In those latter clips, Greenberg as an old man still has the same mental and physical focus so evident in the black-and-white game clips scattered throughout the movie. When he talks about a particular fastball in a particular game that he didn't swing at but should have, you can tell he's thought about it every single day since. As important as being Jewish was to him, baseball meant even more.

That's why he was willing to endure a decade of abuse from fans, other players, even his own teammates. Everywhere the Tigers played, people in the stands screamed racial slurs. Greenberg responded the only way he could—by hitting the ball over and over and over. He was a two-time Most Valuable Player, he almost beat Babe Ruth's single-season home run record and Lou Gehrig's RBI record, he led his team to two World Series titles, and he had a knack for dramatic gestures. He may have been the greatest clutch hitter of all time.

He was also a gentleman who took his public role seriously. He didn't seek his position as an ethnic emissary, but he accepted it and filled it gracefully. The movie tells us little about his personal life (which is kind of a relief in the age of Oprah), but if he was a different man off the field than on it, you can't tell it from the affectionate recollections of his children.

More to the point, it doesn't really matter whether or not he drank or spanked his kids or kissed his wife. He was a Jewish American superman at the dawn of the war against Hitler, a gawky kid from the Bronx who made the extraordinary seem effortless. Kempner's film reclaims a hero for everyone.

October 26, 2000 * Vol. 10, No. 43

© 2000 Metro Pulse

|