Comment

on this story

What:

Hank Williams III with Scott Biram

When:

Wednesday, Feb. 25, 8 p.m.

Where:

Blue Cats

Cost:

$12.50 advance; $15 at the door

|

|

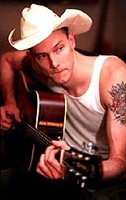

Hank III resembles his granddad, but walks his own path

by Matthew Everett

Hank Williams III released his first album, Risin’ Outlaw, in 1999. Critics raved about his songwriting, and everybody noted how much he looked and sounded like his late grandfather. His high-pitched, nasal twang sounded like a call from the grave, and with his long hair pulled back in a ponytail underneath a cowboy hat, the physical resemblance was striking and eerie. On top of that, his apparent taste for hardcore honky tonk music raised hopes that so-called real country music might be made in Nashville again.

Five years later, though, Hank III has yet to cash in—commercially or artistically—on his legacy. Instead, he’s been touring the country almost non-stop, performing at bars and small clubs with his own bands (the country Damn Band and the rock combo AssJack) and playing bass with the underground metal super group Superjoint Ritual. A contract dispute with his label, Nashville’s Curb Records, has stalled his recording career. The momentum he had five years ago as a sort of novelty recreation of Hank Williams has come to a dead stop. Lovesick, Broke and Driftin’, the follow-up to Risin’ Outlaw, was released in 2002, but another complete CD—this one recorded with his heavy rock band, AssJack, and titled This Ain’t Country—sits on a shelf somewhere in Nashville, and likely won’t be issued anytime soon.

“It’s been seven years of my life,” Hank III says, sitting in a guitar shop in Cleveland a few hours before a gig. “I should already have five albums out, two rock records and three country. I’ve had two releases in seven years. It’s not rocket science.”

Part of the problem is that Hank III isn’t the honky tonk purist that many people took him for when Risin’ Outlaw came out. As a kid, growing up in Nashville, he was a drummer. He got his first drum set and a bunch of Kiss and Black Sabbath records when he was 10, and played in a succession of heavy metal and punk bands with names like Shred, Buzzkill and Rift.

“[My grandfather’s music] was always around,” he says. “I always listened to it. But you get old early in rock. You only have a certain number of years. My plan was to rock out as much as I could and then do blues and country when I got older.”

When he says “rock,” he means it. The Hellbilly side of Hank III, as he calls it, isn’t twangy alt-country. It’s pits-of-hell thrash, with shredded-throat-scream vocals and songs with titles like “Stoned and Mental,” “Go Fuck You,” and “Mary Fuckin’ Jane.” The title of his unreleased record says it all—this ain’t country.

But his rock dreams got sidelined in the mid-’90s after a brief relationship led to the unexpected birth of his first child. “I was in five different bands until I was 20,” he says. “Then a judge told me playing music wasn’t a real job.”

Faced with child support payments, Hank III finally turned to country music, guessing that it would pay better than screaming hard rock, especially given his family connections. In 1996, he recorded Three Hanks, a strange album—now, thankfully, just a footnote—that spliced his voice alongside his father’s and grandfather’s on digitally edited versions of “I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive” and “Move It On Over.” Then came Risin’ Outlaw, a straight-up traditional country record that Hank III almost immediately disowned. For Lovesick, Broke and Driftin’ he tried to wed the spirit of his hard rock with a batch of his own country songs.

And that’s about it. Curb sat on This Ain’t Country and Hank III’s holding out on a country follow-up. He allows video and audio recording at all of his shows and periodically distributes bootlegs on his Web site.

Hank III sees himself as part of a new generation of country music outsiders, like the Outlaws of the 1970s, fighting against Nashville’s commercial pop hegemony and—almost predictably—railing against current Nashville stud Toby Keith.

“We’re the outlaws of the young generation,” he says, aligning himself with fellow honky-tonkers Wayne Hancock and Dale Watson. “We’re a whole new breed. Just because we’re not on CMT or the radio doesn’t mean we’re not out here kicking. We’re totally politically incorrect.”

And yet he’s not a total outsider. He and his Damn Band have performed several times at the Grand Ole Opry to great acclaim from about as conservative a crowd as can be found anywhere. “They know what’s up with me,” he says. “I know how to show respect when I need to, and that’s the mother church of country music.”

February 19, 2004 • Vol. 14, No. 8

© 2004 Metro Pulse

|