Comment

on this story

|

|

The beauty and insanity of poets

by Jeanne McDonald

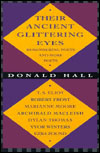

Those who read or write poetry generally delight in the ancient assumption that great poets are slightly mad. Certainly there are dozens of examples to prove the point: Edna St. Vincent Millay, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Robert Lowell, and many of the seven poets Donald Hall interviews in his exquisitely written book, Their Ancient Glittering Eyes (Ticknor and Fields, $22.95).

Whether madness begets poetry, or poetry begets madness, in the 1950s and '60s, McLean Psychiatric Hospital in suburban Boston became a fashionable haven for mad poets, thus rapidly perpetuating this romantic notion.

Although Hall's book is not a deliberate study of madness, a great deal of it is documented in Their Ancient Glittering Eyes. Hall became acquainted with depression as he watched his wife, poet Jane Kenyon, suffer through many debilitating bouts. His empathetic interviews were written over the years as he gained accessibility to the great poets through his own growing celebrity. Marianne Moore was the most puzzling of them all. "Frail, strong, enigmatic," Hall calls her. Her living room in Brooklyn was a "big light room" with piles of books "tottering beside chairs" and "walls covered with paintings...The room was gloriously cluttered, pictures on the wall scissored from magazines, figurines, unidentifiable objects apparently of a natural provenance, and many small effigies of animals." A trapeze hung from her kitchen door. "Objects...arrived in the mail with regularity: someone in Oregon spotted a beetle encased in clear plastic, and thought, "This looks like something Marianne Moore would write a poem about." Although she often misquoted other poets and made errors of fact, Moore knew all sorts of esoteric facts about subjects like baseball. Despite Moore's wild eccentricity, Hall writes: "Removed from the distractions of time, her work grows firmer, her character more luminous, brave, exemplary, virtuous, and strange."

When a junior at Harvard, Hall first met Dylan Thomas in 1950. "Behind the lectern stood a small unsmiling figure, big belly, pudgy face, nose like the bulb on a Klaxon horn, chinless, red-faced, pop-eyed, curly-haired, with an expression at once frightened and insolent. Out of this silly body rolled a voice like Jehovah's. Or Ocean's, or Firmament's. R's rolled, vowels rose and fell...consonants thudded and crashed and leapt to their feet again." On that day Hall heard Thomas read the Yeats poem, "Lapis Lazuli," which gives his book its title: "Their eyes mid many wrinkles, their eyes,/Their ancient, glittering eyes, are gay." But after his rapturous performance, Thomas slid into what his Swansea friends called "Instant Dylan," drinking himself into a nasty mood, insulting women with sexual innuendos, and drunkenly proceeding to the next reading, and the next. "I suppose," Hall ruminates, "that his gregariousness was another refuge from pain, the anesthesia of promiscuous acquaintance, like drinks, anesthesia that slid toward death...laughter and death and public suicide."

In the case of T. S. Eliot, it was his wife, Vivien, who became mad. In 18 years of a reckless, unsuitable marriage, the pair fed off each other's instability. "It is traditional to understand," says Hall, "that poets may well be punished like Prometheus for an impious gift. Some people court their own punishment by falling in love with it or by marrying it...[The] intensely creative woman who loves the neurotic, possibly psychotic man...can not live or work without him..." Eliot married "Maybe...in order to be impotent, to suffer, and to write poems. When he separated from her, he chose a monastic grief, out of which he wrote his best work in Four Quartets." Vivien died in a London mental hospital 15 years later, but in old age, Eliot "found honor, joy in a second marriage, and died full of years and glory."

Under a Stanford fellowship, Hall studied with Ivor Winters, a man who had feared madness all his life. In Forms of Discovery, Winters wrote, "A psychological theory which justifies the freeing of the emotions and which holds rational understanding in contempt appears to be sufficient to break the minds of...men with sufficient talent to take the theory seriously. Conversely, such a theory tends to equate irresponsible behavior and even madness with genius."

Ezra Pound was indeed certifiably crazy, but Hall praises him for his support of other poets, particularly H. D. and William Carlos Williams when the three were students at the University of Pennsylvania. "Pound discovered a thousand ways to make a noise," Hall exalts, deriving from "the weird combination of Sappho's euphony and a Viking drumbeat."

The most universal poet Hall portrays in this book is Robert Frost, who, although a popular national favorite, was jealous of all other poets, especially T. S. Eliot. Like Dylan Thomas, Frost performed "in order to be loved," claims Hall, who recognized two versions of the stalwart old poet: "a smooth performer who manipulated an audience by playing up to it, the other a jealous literary god blasting his enemies." Burdened with so many personal disasters, Frost lived in terror of madness and suicide; but while Anne Sexton "marketed her suffering, for a morbid audience; he denied his suffering, for a sentimental audience."

"If we admire the poem," Hall says in his introduction, "it is natural to be curious about the poet." Thus, this book is a shimmering gift to anyone who has ever felt a poem touch his heart. Hall's treatment makes these poets seem more approachable and more earthly; still, they remain a bit more elevated than the rest of us because of their incomparable poetic powers.

May 15, 2003 * Vol. 13, No. 20

© 2003 Metro Pulse

|