Comment

on this story

|

|

Tales of the New South can still have the old darkness

by Jeanne McDonald

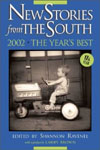

There are plenty of people below the Mason-Dixon Line who still call the Civil War the "War of Northern Aggression" and who still believe the South will rise again. And in a way, it does, once a year, when editor Shannon Ravenel publishes her annual New Stories from the South (Algonquin, $14.95).

In this, the sixteenth edition, Lee Smith, the quintessential southern writer, writes a funny and informative preface that finally delineates the difference between writing about the Old South and the New South. Previous writers who have tackled the dissimilarities have stumbled abysmally, but  Smith gets it right: "The South was two-thirds rural in the 1930s," she writes. "Now it is over two-thirds urban.... As the largest metro areas continue to attract people and jobs, the viability of rural life comes increasingly into question. One half of all the new jobs in this country are being created in the South...and in the 1970s more blacks started moving to the South...(rather) than leaving it." And, she says, "our per capita income is at 92 percent of the national average." Smith gets it right: "The South was two-thirds rural in the 1930s," she writes. "Now it is over two-thirds urban.... As the largest metro areas continue to attract people and jobs, the viability of rural life comes increasingly into question. One half of all the new jobs in this country are being created in the South...and in the 1970s more blacks started moving to the South...(rather) than leaving it." And, she says, "our per capita income is at 92 percent of the national average."

So what do all these changes mean for southern writers who still define stories about the South as "the literature of nostalgia," a term coined by Allan Gurganus? Undoubtedly, they have to turn to new themes, new settings, and new characters instead of depending on the old formats. "...[N]eurasthenic, fragile Aunt Lena is already trite," says Smith, "her mean, scary cousin Bobby Lee is already trite, her columned, shuttered house in Natchez is already trite. Far better to start out from the mall in Fayetteville, illicit cigarette in hand, with no cousins to hold [the writer] back, and venture forth fearlessly into the New South."

And so they do, many we don't yet recognize, and others, like John Barth and William Gay, whose work we know well. In the opening story, "Where What Gets into People Comes From," author Moira Crone says that she uses the stories that came out of her childhood in North Carolina, at a time when people knew each other's secrets and spent time learning about their neighbors. "Southerners my age have this in common," she says, "we were raised in a pre-psychological age. We come from the past."

I, too, was raised in a southern town in coastal Virginia where you knew everybody in the neighborhood. There was no air conditioning then except in department stores and movies, so, in the summer, through screen doors and open windows, you could hear family arguments, the clatter of pots and pans, babies crying, piano exercises—people living out their very lives. Because information never stayed secret for very long, you knew about the evil, too—the man on the next block who abused his two daughters and was finally sent to jail, and the neighbor whose dark behavior led to his daughter's suicide: At age 18, she hanged herself in their garage, just down the back alleyway from our house. We tolerated the old men who teased us, ran from the retarded boy whose mother could not bear to put him in an institution, roamed freely in woods and on water. We rode our bicycles and memorized our own internal maps of the neighborhood.

Now, sidewalks have dis-appeared. Mothers work. We close our doors to keep the air conditioning inside. Families are insulated. Teenagers and prepubescent children roam the malls. They smoke grass and experiment with sex. These are some of the social issues that the work of Southern writers must  now reflect. Among the stories in this collection, a car wash serves as one setting, a mall in another, and a nouveau riche mansion in a terrifying story by William Gay called "The Paperhanger." Not one of these stories is trite, not one resorts to using Bobby Lees, antebellum mansions, or crazy aunts. now reflect. Among the stories in this collection, a car wash serves as one setting, a mall in another, and a nouveau riche mansion in a terrifying story by William Gay called "The Paperhanger." Not one of these stories is trite, not one resorts to using Bobby Lees, antebellum mansions, or crazy aunts.

Except for religious books and self-published manuscripts, sentimental and melodramatic stories are passé today, as evidenced by the stories of Lisa Teasley in her collection, Glow in the Dark (Cune, $23.95). Although many of these stories will make you uncomfortable, even disturbed, Teasley's dark, edgy sketches represent the sick and disenfranchised people of America's big cities. Characters who are weirded out, high on drugs, self-destructive and incestuous stumble through the pages of her book. These stories are more about mindscapes than reality; in fact, the entire book has a surrealistic feeling, yet Teasley shows enormous compassion for her characters, even the worst ones, people who are breaking down, breaking apart, breaking up.

She follows them fearlessly into dangerous streets, reveals to us their hopeless dreams, makes us watch when they overdose and kill themselves. Yet, these taut and economical stories compel us to examine the underbelly of our society, to think about people we might deliberately rush by on the street. When you close the last page of Teasley's book, you will feel uneasy about these characters, but you will never forget them.

June 27, 2002 * Vol. 12, No. 26

© 2002 Metro Pulse

|