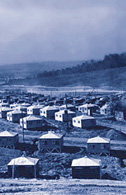

Photo by Kimberly Jones Bell

Comment

on this story

|

|

The city strives to change its image from one that glows in the dark to one that shines in the light.

by Barry Henderson

When a city is born in a flash, as Oak Ridge was in the 1940s, there is a risk that it will begin to disintegrate all at once. Many Oak Ridge leaders conclude that such a breakdown, spurred by shifts in the local economy and employment patterns, began to be felt in the city in the late 1990s. Fifty years of deterioration was taking its toll on infrastructure and housing stock that was originally intended to endure for a mere seven years.

As the '90s wound down and the new century cranked up, the economy leveled out and now has started to grow again, with new jobs and the prospects for more materializing almost daily. In that light, a new breed of Oak Ridger has begun to exert influence toward "reinventing" the city. That view is held by an assortment of natives and new arrivals who are enamored with the community's lifestyle and its significant cultural advantages and are fearful that neglect of a few vital issues might ultimately drain the city of its very viability. Those new leaders are saying drastic measures need to be taken to improve Oak Ridge's image, its housing stock, its shopping and job opportunities and, with those latter three, its property and sales tax base. Otherwise, they say, the proverbial end may be near.

After talking with some of the progressive new breed and some skeptics, who include a sizable group of retirees anxious to keep taxes in line with their fixed incomes, it's difficult to see an easy or inexpensive way out of Oak Ridge's dilemma. The list of options on the table, though, is impressive. It includes projected improvements in shopping, in housing, even in the school system, which is already considered among the finest in the state and is the greatest single draw the city holds for young families.

The city is, in fact, taking drastic steps to head off the perceived municipal calamity. Just last week a controversial $23.2 million bond issue gained support from a City Council majority. The bond proceeds are to be used mostly for improvements in the center of town, where a mall containing Sears, Penney's and Proffitt's department stores and a host of smaller shops is failing. The sales tax revenues from such a retail core are essential to maintaining Oak Ridge's fiscal balance, the bonds' proponents argue.

The question of what to do to change the mall's fortunes is complex, but the Council majority clearly favors a proposal to take off its roof and replace it with a Main Street intersection. The three major tenants would be retained and much of the remaining retail space would be filled with specialty shops and offices lined along a traditional "village" street. The city would provide money for two streets, curbs, speed bumps, lighting and landscaping, to the tune of $6.5 million. It would also establish a new city schools' administration building, a city services building and a senior citizens' center on mall property (to be acquired later).

The developers, Oak Ridge City Center, LLC, a group led by Chattanoogan Steve Arnsdorff, would purchase the rest of the property and perform the design and construction/rehabilitation of the "village" retail space. The developers' plans are contingent on gaining extensions of the Sears and Penney's leases, which expire within the next four years. Without some incentive such as the proposed streetscape, the department stores are expected to let their leases lapse and leave the mall and the city. Proffitt's lease runs to 2013, but it could not anchor a mall or shopping district on its own.

Mall Mania

The city's payments toward rehabbing the mall area have caused an uproar, because they are viewed as a tax-supported subsidy that bails out the current mall owners as well as partially funds the new developers' plans, with no guarantee of return in the form of increased sales tax receipts.

But the Council majority, which also passed an 11 percent property tax increase two months ago, stood firm on the bond issue. At the Council meeting May 6, a parade of older Oak Ridgers took the podium to oppose the bond issue's mall rehab purposes. They had placed "house for sale" signs on each seat in the gallery, implying they would move out of the city if the bond issue passed without a referendum.

Once the vote was taken, opponents proceeded to organize a petition drive, which would require gathering about 1,800 signatures of Oak Ridge voters in less than three weeks, to force a referendum vote. Their chances of succeeding aren't yet clear. The Council majority clearly views the opposition as a potential impediment to the city's ability to get through these tough economic times intact. The opposition, on the other hand, is worried that the city can't spend its way out of the mire, and its concern with the state's highest city-county combined property tax rate (depending on how one views the Memphis-Shelby County rate from an equalization standpoint) is well justified. Steve Jenkins, the assistant city manager who specializes in finance issues, says the city's bond indebtedness exceeds $100 million, including electric, water and sewer bonds supported by user rates. The water and sewer bonds were needed in part to fix old temporary lines that were breaking down. Debt service on general obligation bonds that rest primarily on tax collections costs about $4.6 million annually. That cost is expected to rise only to about $5.1 million a year with the new bond issue, Jenkins says. That's still nearly a sixth of the city budget, and opponents are predicting property taxes will go up about 9 percent per year over the next four years, partly because of the new debt.

Mayor David Bradshaw, who is elected by Council colleagues, and Council members Ray Evans, Tom Beehan and Jerry Kuhaida form the majority pushing for the city action and expenditures. Council members Willie Golden, David Mosby and Leonard Abbatiello form a minority with a more conservative approach.

Abbatiello, one of four Council members with graduate degrees (all are college graduates) leads the minority. He's quick to react to the assertion that it's the progressive faction vs. the conservatives— those who've shown caution, if not opposition, toward any initiatives that would raise the property tax rate. Though the minority tends to represent the retired segment, which exceeds 20 percent of the city's population, Abbatiello says, "A lot of those people are progressive. Don't get them wrong. They're looking for efficiency and effectiveness in government."

A sober, bespectacled Y-12 nuclear weapons plant engineer who grew up in Oak Ridge, Abbatiello acknowledges that "there's no question the mall is a disaster." He questions the concept that the Main Street incarnation would draw shoppers from Morgan, Fentress, Scott, Campbell and Roane Counties, nearly 150,000 strong, as envisioned by the developers and their proponents.

Those outlying shoppers once relied heavily on the Oak Ridge market place, before the advent of Wal-Mart Super Centers and Big Lots stores that now provide broad selections closer to home. The Wal-Mart adjacent to Oak Ridge Mall, a Super Center, does well in fact, but the Main Street proposition is for a greater variety of specialty stores and upscale retailers to complement the department stores. The idea is to lure Oak Ridgers and residents of the northern tier of counties back to shop in "The Village" instead of West Town and Turkey Creek and the rest of the Kingston Pike Corridor. Equally important, the concept is designed to provide a fresh reason for new families to live in Oak Ridge itself.

Abbatiello and his colleagues in the controversy are averse to risking tax money on the project. He says he advocates free-market redevelopment of the mall "without subsidy." The city's effort should be toward a "much less costly modification and remarketing strategy," Abbatiello says.

The Crown-American Oak Ridge Mall was never a rousing success, and the downturn in the city in the late '90s has left it in a state that several Oak Ridgers referred to as a "ghost town" or a "place for old people to walk." Indeed, the first response to the proposal to remove its roof and its climate controls was a set of letters to the editor of the daily newspaper, The Oak Ridger, complaining that "we won't have any place to walk." Parker Hardy, president of the Oak Ridge Chamber of Commerce, which backs the Oak Ridge City Center proposal, says the community's needs do not include "a $55 million walking track."

ORCC's Arnsdorff, who has been involved in the acquisition and renovation of mall properties, mostly in the Southeast, since 1994, is eager to get started setting up what he calls Oak Ridge's "first real downtown."

With steely blue eyes and a shock of rusty, Kennedy-esque hair, Arnsdorff dances and gestures around a table of conceptual drawings of the project in the offices of the Oak Ridge Chamber of Commerce like a recreation director on a cruise ship, blue blazer and all. He says his group's financing for the project is in line, awaiting final commitments from the city and the anchor tenants. He's optimistic that the new shopping district can be up and running in time for the holiday season in the late fall of 2003, so long as there are no major setbacks. A referendum would set it back "a minimum of six months," Arnsdorff says. He says Hibbett Sporting Goods of Birmingham has committed to a 5,000 square-foot outlet in the ORCC scheme of things.

"If it goes, it goes," says Tom Beehan, a Council member and former mayor of Covington, Ky., who has seen developers' dreams come and go, some to great heights and others up in smoke, over his career in public service. Knoxville regional manager for State Farm Insurance, Beehan says he's confident that there will be a mall renovation of some kind, but that's not the only shopping improvement the city is encouraging.

Six months ago, Council passed an innovative zoning ordinance that encourages the establishment of small shopping areas alongside new subdivisions to put everyday essentials within walking distance of residences.

Mayor Bradshaw says Oak Ridge was originally laid out by the famed Chicago architects Skidmore, Owings & Merrill around the concept of locating schools and shopping at an easy walk from each of the neighborhoods. Expansion in the 1960s got away from that concept, but recently a 1,000-acre former Boeing site near Oak Ridge's western edge was bought for a combined housing/shopping development called Rarity Ridge. Mike Ross, the Maryville developer whose successes include Rarity Bay along Tellico Lake south of Loudon, provided the impetus for the new zoning ordinance. Bradshaw says the ordinance has attracted attention from other developers whose interest is in "new urbanism" ideas that are, at least partly, a throwback to the old urbanism that was built into the Oak Ridge design.

Scattered shopping, however, is not nearly so important to any resurgence in the Oak Ridge economy as is new housing across a broad range of styles, prices and rents.

Besides concerns about outsiders' perceptions of the city as a government town with residual contamination problems, housing is the No. 1 issue on the agendas of the City Council, the Chamber and the assorted bootstrap organizations that have cropped up to advocate technology transfer from Department of Energy contractor installations to private companies, either existing firms or start-ups.

Housing Woes and Wants

The housing stock in Oak Ridge is as bizarre an assortment as one can find. More than 6,000 of the city's 12,000 occupied housing units are from the World War II and immediate post-war era. They were erected by the federal government in classifications from A through H, including single-family, duplex and four-plex versions with flat roofs, built of prefabricated panels made of Cemesto, a mixture of cement and asbestos applied to a fiber core. Their advantage at the time was that they could be tossed up in a day. Intended to be temporary, they were as small as 800 square feet and were assigned by family size. None are large by today's standards. The asbestos component, sealed in cement, is safe so long as no dust is raised from the panels by cutting or drilling, which would create a health hazard to anyone breathing the dust. Oak Ridgers seem confident of that.

Some of the so-called Cemestos have been extensively remodeled to include gabled roofs, add-ons and even basements. Some are still in their original state. Perhaps as many as half should be demolished and replaced, the younger and more progressive element of the community believes, because of their condition and the advantageous location of the real estate beneath them. But most are occupied, either by owners or renters, and acquisition would be a difficult, lengthy and costly process.

A newly adopted building code with "teeth in it" should facilitate the condemnation of a few and the upgrading of some more, at least as they change hands. A survey based on that code of 1,000 homes in the desirable Highland View neighborhood is to be completed by volunteers, and the results will be weighed to determine how best to cope with the overall situation, according to Councilman Beehan, chairman of a housing task force he initiated for the city.

In terms of square footage and built-in amenities, "A house that was right for a family [here] in 1950 is not acceptable now" to families thinking of relocating to Oak Ridge, says Ray Evans, the executive vice president of Barge Waggoner Sumner & Cannon, a leading engineering firm in this region.

Indeed, the generation of scientists and engineers who first inhabited those odd little structures fixed them up and made them as comfortable as possible, foregoing more elaborate physical surroundings in a trade-off for the cultural and social climate and the school system, which they helped build into a model. The originals mingled happily with their own; they created and supported the ballet and symphony, and they are now retired or gone.

Evans, who grew up in Oak Ridge and was elected to Council three years ago, formerly served on the city's planning commission. He says Barge Waggoner architects are developing a set of plans to rehabilitate and remodel the Cemestos, with three different plans for each type. The plans will be made available to owners for free, and Home Depot has agreed, unsurprisingly, to put together packages of materials matched to each plan. The improvements will be significant, but the units will still be small, relative to suburban trends.

New housing is a different matter altogether. Evans believes the city needs initiatives to encourage a mix of new homes priced between $90,000 and about $300,000. Most others agree that the dearth of new mid-range houses, priced between $200,000 and $250,000, is the most pressing problem. But Abbatiello also points out that there are currently very few "high-end" apartment rentals available for prospective new residents. Instead, they tend to settle initially in the West Knoxville area while looking for a permanent home, then become familiar with their surroundings, get used to what's become an easy commute on Pellissippi Parkway, and buy there—in Farragut, Concord, Karns or West Knoxville itself. Meanwhile, Abbatiello says, 18 percent of Oak Ridge's rental units, mostly older apartments and duplexes, stand vacant, unwanted and deteriorating.

Land for new housing in the city is also at a premium. The city comprises 92 square miles, an area comparable to Knoxville, but more than half of that is under federal ownership, and much of that federal land is very rugged and even unbuildable. When the United States was siting its massive, secret plants there, it put the gargantuan buildings in valleys, separated by ridges that served as security buffers. Although some of the old plant sites are now unused and may be suitable for industrial purposes once they are cleaned up, they are not deemed prospective housing tracts.

There is a subdivision of nice, newer homes called Westwood on land the city owned west of downtown, but it is nearly built out. A city initiative on 800 acres termed "Parcel A" to the east along Melton Hill Lake was to have created up to 1,000 housing units arranged around a city golf course called Centennial. It may yet be thought of as successful, but disagreements with the original contractor led to litigation and delays and embarrassment. A couple of hundred homes have been built in the area, but most are at the top end of the price scale. The city is now trying to find a builder or builders willing to contract for the remaining 250-300 acres.

Councilman Jerry Kuhaida explained at last week's meeting that title to a former security buffer zone of 1,000 acres designated and already developed with high-quality infrastructure as an industrial park called Horizon Center should be passed directly from the federal government to the non-profit Community Reuse Organization of East Tennessee (CROET), rather than be held by the city. In his argument, Kuhaida said, "The city's record of property management is not great." It was a direct reference to Parcel A and was met with laughter from those on both sides of the issue.

Last June, Evans says, a jointly formed DOE/Oak Ridge Land Use Committee began taking recommendations for the future of another 1,000 acres at the far west end of the federal reservation that might be suitable for housing. The committee, on which he serves as Council representative, is "about evenly divided between pro-development and environmentalist interests," and the recommendations range from no development to "moderate" reuse, with no consensus, he says. Wildlife and wildflower considerations have kept the potential reuse profile low there.

Inertia on such land issues dramatizes what's become a virtual housing crisis. Abbatiello says the current employment pool is expanding by 500 jobs a year, but only a tiny fraction of new employees pick Oak Ridge for their home. The jobs now in place "may as well have been someplace else if we don't have the housing," says Beehan. Still, the employment growth is a welcome change.

Reversal of Fortunes

In their tumultuous wake, the Department of Energy's mid-'90s layoffs of thousands of workers left a series of opportunities that have been gradually coming to the fore.

DOE contractors in Oak Ridge, including those managing the rejuvenated Y-12 weapons plant (now called a national security complex, with about 4,500 workers), and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, which employs 4,000, are increasing their staffs. The total federal and contractor payroll for 2001 grew 6 percent from the previous year to $767.4 million. The hitch is that less than $200 million of that amount was paid to workers actually living in Oak Ridge. It's a city that holds 27,000 residents and hosts 15,000 commuters every workday. Roane and Anderson County residents outside Oak Ridge proper picked up about $150 million of that payroll total, and Knox Countians working there were paid a whopping $324 million. The rest was scattered among commuters from across the region.

ORNL has been growing rapidly since the UT-Battelle public/private consortium took over its management contract in 1999. Its annual budget, which was about $600 million three years ago, approaches $1 billion in 2002 and will probably exceed that next year, according to director of communications Billy Stair.

The heralded national Spallation Neutron Source (now about half completed), a new fusion energy research component, an enduring program of environmental research and anticipated increases in nuclear energy research should fuel ORNL's future employment engine to the tune of about 500 to 1,000 more staff positions within five years. A $1.7 billion modernization program, including 14 buildings, is under way, with 250,000 new square feet of workspace under construction. The upgrades are being paid for mostly by the federal government, but the state is investing $26 million, and private capital investment of $72 million is included, according to Bill Madia, UT-Battelle president and CEO and ORNL director.

Madia gets lots of the credit for enhancing the lab's outlook. "Like a quarterback, in this position you get more credit and more blame than you deserve," he says. But his vision for ORNL is to solidify its position as the premier energy and science laboratory in the nation and, through its existing nuclear reactor technology and the Spallation Neutron Source, to become the world's foremost center for neutron science.

ORNL spin-off technologies continue to find placement in Oak Ridge with assistance from the non-profit Tech 2020 business incubator and other such organizations.

CROET (which was reputedly first designated the East Tennessee Community Reuse Organization until someone noticed that the acronym, all-important in Oak Ridge's alphabet soup of agencies, boards and commissions, would be "ETCRO") is actively pursuing tenants for former DOE spaces.

Larry Young, president and CEO of CROET since it was formed in 1995, has been leasing facilities from the DOE as they become available and subleasing them to commercial and light industrial tenants. The current leases cover about 500,000 square feet of space, with about 70 percent of that let to a total of 40 tenants who provide about 400 jobs.

Although part of the K-25 plant site has already been subleased, its mile-long main building must eventually be demolished to make room for adaptive reuse of the land. And the whole reuse process has been complicated since September 11 with security clampdowns on the site, which have caused such inconveniences as the rerouting of a Secret City excursion train that had been rolling on rails through the property. Young is practically salivating at the prospect of redeveloping the old K-33 plant, a uranium processing facility that is nearly completely cleaned up and decontaminated by the DOE contractor BNFL, Inc. The building itself covers 33 acres and is ideally suited for a major manufacturing enterprise.

There are, in fact, bright industrial prospects for several parcels of DOE land, but the day has not quite yet arrived. What Oak Ridge still relies on in large measure are the 20 technological, scientific research and engineering companies, including a half-dozen primary DOE contractors, that employ 100 or more people in positions that pay excellent salaries across the board.

Going to School

Oak Ridge used to describe itself as having more PhDs per capita than any city in America, and it was probably true. Today's Chamber of Commerce assertions include Knoxville when pointing out that there are about 2,500 PhDs in the Oak Ridge area.

In spite of ups and downs tied to DOE project start-ups and layoffs, the total population figure has remained remarkably flat. Though estimates showed a dip to around 24,000 persons in the mid-'90s, the 2000 census showed 27,300 residents, virtually the same as in 1990 and only 1,000 fewer than in 1980. What's changed most are the median age, now well above 40, and the number of persons over 65, approaching 25 percent of the total.

What that means for the education system is fewer parents of school-age children in the mix. Oak Ridge High School, which once had more than 2,000 students, is now serving a little fewer than 1,500. Its campus-style buildings, seven in all, date mostly from the 1950s and are in need of renovation or replacement, a difficult proposition when the tax structure is already stretched taut. But there is a strong likelihood that the high school will be given the attention it needs.

From the outset, the school system has had an excellent reputation. The scientific community demanded and was willing to pay for that, and their children were well prepared for top quality schooling. The system attracted superior teachers, many of whom are now retired or nearing retirement.

"In my tenure here, replacement of teachers who are institutions will be the biggest thing I do," says Ken Green, who moved from principal of Knoxville's West High School to Oak Ridge High two years ago. Green went to school in Oak Ridge himself.

"In Oak Ridge we have a culture that is committed to learning as well as teaching. Teachers who have stopped learning don't fit in, and they leave or we get rid of them," Green says. He says constraints on teacher pay brought about by the state's budget crisis won't necessarily disrupt his school in the short run. He calls himself an "avid and aggressive recruiter" who sells his school through his own teachers' conception of priorities and their communication with prospects. He says he continually asks himself, "Are my teachers here professionally satisfied with their environment?" He thinks the answer to that is yes more often than not.

"There is a misconception that we get better teachers because we pay better," Green says. "Pay is a factor, but a bigger factor is if teachers are treated as professionals...[and] are given the discretion to make professional decisions within their area of expertise."

He says his school is "very diverse, more socio-economically than by race," the latter of which is 85 percent white, 11 percent black, and about 2 percent each Hispanic and Asian. He sees a difference in school readiness of today's incoming students, who are "more in need of remediation" than in his previous experience as a student and teacher, and that the preparedness shortfall runs across the socio-economic scale. But he also says those who come up through the grades in Oak Ridge have much more exposure to such subjects as music and art than do most high schoolers in the region because of Oak Ridgers' commitment to the humanities as a fundamental part of education.

Maintaining the Oak Ridge Symphony has been a remarkable achievement for a community of fewer than 30,000 people, as has keeping up the high standards of the Oak Ridge Ballet and the Oak Ridge Playhouse, a theater group that dates from the 1940s. The schools' emphasis on the humanities is a reflection of those cultural enterprises, and vice versa.

Not surprisingly, the school system also emphasizes the sciences, and ORNL's Bill Madia says the lab is in a position to contribute equipment and teacher retraining for science courses. He also says the lab's contractor, UT-Battelle, has made a commitment to contribute financially to a new high school. "We want Oak Ridge High School to be the finest science high school in the country," Madia says.

With that kind of backing, in this kind of community, Principal Green's confidence seems well-founded. He points out that the schools are attracting increased numbers of Knox County students—35 to 40 in the high school and about 100 systemwide—whose parents pay tuition of more than $4,000 per year for the privilege.

Besides the vaunted schools, Oak Ridge takes advantage of its picturesque hills and dales and the Clinch River valley's Melton Hill Lake in the form of marked miles of walking and bicycling greenways, broad manicured parks and one of the nation's finest competitive rowing courses.

Part of the motivation to show itself off environmentally is undoubtedly based in the concerns outsiders show regarding the 50 years of work in nuclear technology and the risks associated with ionizing radiation and the levels of sidestream chemical contamination that showed up in the early 1980s.

There may be no city anywhere that has seen the amounts spent in environmental clean-up that Oak Ridge has. But tens of millions of government dollars and untold man-hours using the most sophisticated removal methods for contaminated equipment and waste materials won't erase the perception that, in the words of one Oak Ridge advocate who said he was quoting unspecified Knoxville real estate sales people, "it might be OK to work there now, but you wouldn't want your family to live there."

ORNL's chief, Bill Madia, wants his family to live there, and they do. "There's a message there that this is a community of hope...a community with a future," Madia declares. He says the leadership has a responsibility to convey that message.

The Path Forward

To that end, City Council got together several times outside the regular meeting schedule in the last few months and ultimately adopted a "strategic plan" to guide the city between now and 2005.

The objective was to help the city become "an exceptional place for all to live, work and visit." Ray Evans says the significance of the plan is in the Council's agreement to follow it, and Tom Beehan says the common agenda "to become active instead of reactive" is "one of the things that makes me optimistic."

There were four "critical outcomes" outlined in the plan, and each has elements that appear to be out of Council's control.

To "achieve a property tax rate that does not exceed the 75th percentile" of comparable cities by 2005, for example, the city must rely heavily on prospects for the success of an initiative toward getting higher payments in lieu of taxes (PILOT) from the DOE. The city has retained Knoxville lawyer Bob Worthington to negotiate new terms with DOE, which currently bases its $1.1 million annual PILOT on agricultural value of its land, but charges market value, four to five times greater than the ag value, when it sells land to the city. The goal is to reach a compromise payment level of about $4 to $6 million per year, but there has been no report of progress, and DOE has not been historically generous in that area.

The housing outcome has an objective of increasing housing starts by 25 percent. In an arena as market-driven as new housing construction, that may be a difficult trick. Meeting that mark will hinge on other, "quality of life" goals, which call for addressing "some negative perceptions about the area" and stipulate economic development, including better shopping attractions. None of those areas can be directly manipulated by city government, but the city can serve as a facilitator for such actions, Mayor Bradshaw believes.

However the strategic plan turns out, Oak Ridge will be a place unique in the Eastern United States for its almost incredible founding, its grappling with environmental problems in the midst of a panorama of natural beauty, and its concentration of scientific minds. It was built by engineers. It's being run largely by engineers. Now they have to see if they can engineer the city's way beyond its mounting problems.

May 16, 2002 * Vol. 12, No. 2

© 2002 Metro Pulse

|