|

Comment

on this story

|

|

The Plague infects the lower South and the upper Midwest

while our intrepid writer drives

by Matthew T. Everett

Riley's Rock House is a steel-belted heavy metal bar in Aurora, Ill., a working-class suburb on the western side of Chicago. As I walk in with the members of the American Plague at 9 p.m. on Friday, Oct. 12, we all four exchange glances of trepidation. The bar's full of roughnecks with mustaches, swilling cheap beer, wearing NFL jerseys and death metal T-shirts. Metal blasts from the jukebox, and the waitresses, with frazzled bleached-out hair and spandex dresses, don't seem to have updated their personal styles since the mid-'80s.

There's a poster on the wall advertising an upcoming show by Flotsam and Jetsam, the journeyman speed metal band best known for their former bass player, Jason Newsted, who went on to stadium-packing fame in the '90s with Metallica. A flyer for tonight's show lists the American Plague—"From Memphis!"—along with the names of three other bands, none of which offer any comfort from the overwhelming hesher atmosphere: Bludgeon, Dark Ritual, and God Help Us.

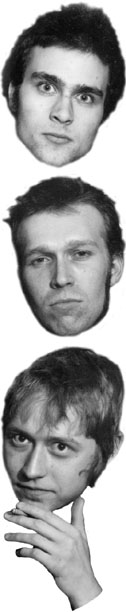

Alex, 24, the American Plague's tall and lanky guitarist and singer, and 19-year-old bassist Dave Dammit would probably be all right here. Dave, in fact, is a confirmed metal head, with a fistful of silver rings and a skull dangling from a chain around his neck. Alex is tall and lanky in a rock-star sort of way, and has the confidence of a front man. The band's elfin drummer, B.J. Fontana, and I aren't so lucky. B.J.'s wispy blond hair is cut with thin little forelocks hanging over his ears, and I'm, well, I'm just a skinny writer tagging along on tour.

The sound man, a burly guy of around 40 with a knot of curly hair shooting out from underneath a ball cap and several inches of butt crack exposed from the back of his pants, doesn't deliver any relief from the tension. When Alex asks him if he knows the order of the bands, the sound guy laughs and says, "The odor of the bands? It's pretty high!"

It's hard to believe we drove 17 hours and 1,000 miles in a 1974 Plymouth van for this. We're all slightly stunned, both by the long drive after the previous night's show in Savannah, Ga., and by the prospect of being run out of the Rock House by a mob of metal heads who we're certain aren't going to be impressed by the American Plague. While they play up their own tough-guy rock 'n' roll pose, and probably have more metal and more punk to their sound than any of them will admit, the Plague guys are really just a rock band. They usually play to college and small indie-rock crowds, and are absolutely unsuited for this place, especially when sharing the stage with a band called Bludgeon.

After unloading the van, we head for dinner at a nearby fast food restaurant. On our return to Riley's, we park in the back and walk down a narrow alley to the front of the club. Alex points at a four-foot band of steel reinforcement that's been added to the corner of the building.

"That's where I ran into it the last time I was here, with the Undead," he says, jumping around gleefully as he recounts that night from last year. After a stint in the Knoxville punk band the Malignmen, Alex played drums for the Undead, a horror punk band led by Bobby Steele, a founding member of the legendary Misfits. "We got paid, but none of the other bands did, and they were pissed off, cussing at the manager out here in the parking lot. They didn't know we'd made any money, so we figured we should just get in the van and go, and I ran into it trying to get out as fast as I could."

Alex's story deflates the bad feelings once we're back inside the club. It's like we've already taken a preemptive strike against the mob of metal heads waiting for us.

The show at Riley's falls well short of disaster. In fact, even though only 13 people—including me, the sound man, the bartenders, and the members of Dark Ritual—are still there for the 12:30 a.m. set, the band members consider it their best show of the weekend. The sound man cuts the band off before their usual show-stopping cover of Motorhead's "Ace of Spades," but it's still a tight and spirited effort. They even sell a CD and a T-shirt, pushing their total take for the night up to $90, significantly more than the other bands made. The agency who booked the show gave them a guarantee of $75, minus 10 percent for the sound man, while the other bands, all from Chicago, were booked by the club and only got a percentage of the door. There's something weird, almost absurd, about driving 1,000 miles to play in front of a dozen people and earn less than $100.

Subtract the absurdity, though, and I wouldn't even be here. I've known Alex for several months, and he called one night in August, aware of my temporary summer underemployment, to ask if I'd help them drive for a weekend. B.J. is taking classes at the University of Tennessee this semester, which limits the band to weekend tours, but they've scheduled shows all over the East Coast and Midwest through the end of the year. In January, when B.J. puts school on hold, they plan to spend even more time on the road. Alex had booked an insane itinerary for this particular weekend—Savannah on Thursday night, Aurora on Friday, and then down to Carbondale, in southern Illinois, on Saturday. He accepted the show at Riley's because it was scheduled by a prestigious booking agency, and he feared that he would lose an opportunity if he turned them down. I told him I'd do it, fully expecting to have a full-time job by the time of the tour. As the weeks sped past, no job offers came. So I was stuck.

A week before we left, Alex and I had lunch in Fountain City to discuss some of the details.

"What do you like to eat?" he asked.

"Whatever," I answered.

"Do you like peanut butter?"

"Yes."

"Do you like bread?"

We leave Knoxville at 10:15 a.m. on Thursday, heading across the mountains of North Carolina toward Charleston, then down the coast to Savannah. We trade off the driving, everybody taking a turn of a few hours. Alex guides us into downtown Savannah during rush hour, navigating traffic circles and horse-and-buggy tours until we reach the Velvet Elvis.

The Velvet Elvis is a spacious underground rock club with a large ceiling, a few booths up against the wall and a long bar opposite. After we unload the van, we drive 20 minutes to the beach and walk in the semi-darkness, poking at dead jellyfish and talking about war.

Then it's on to more urgent matters. The club doesn't have a kitchen, so there's no chance of a free meal. Alex suggests peanut butter sandwiches, but the others demur.

"I can't play on p.b.," B.J. says. "I've got to have something in me."

I mention a fast food restaurant we passed on the drive to the beach, and Alex agrees to stop. The band members allot themselves $8 a day for food. Peanut butter and white bread are staples on the road, as are Denny's $2.99 Grand Slam breakfasts. Instead of buying sodas when they stop for gas, they take gallon jugs of water and empty bottles. If possible, they spend the night with people they meet at the shows or with the other bands they play with. Hotels are a luxury. So are showers, as I realize on Friday when we've been on the road for 36 hours, most of it in the van.

The Velvet Elvis stop is a good one, I think. There's a sizable turnout of 50 or 60 people, though most of them wander in and out during the first two bands. Most of them, dressed in black leather and torn jeans, are here to see Krast, a popular local hardcore band that's headlining. The Plague follows a thunderous math rock band from Los Angeles, the 400 Blows, who got a pretty lousy write-up from an uninformed critic in the local weekly paper. I'm tempted to buy a CD, but remember Alex's admonition that they can't afford to buy merchandise from other bands. I don't want to stray too far from band policy. I'm already eating better than them, after all.

During their set, Dave introduces "Chinese Rock," a Ramones/Johnny Thunders song about heroin. "Some of you might recognize this one," he shouts into the microphone. At least one person does, a kid who looks like Zack de la Rocha of Rage Against the Machine. After only a couple of chords, he puts down his backpack and rushes to the stage, pumping his fist and singing along.

Outside the club, as we're loading up the amps and guitars and drums that fill the belly of the van, a drunk and somewhat seedy looking man in his 30s, with a pretty girl on each arm, wanders up to B.J. and Dave.

"I had some friends of mine in a band playing up the street, and nobody came because you guys were playing. I lost $1,100," he says. B.J. and Dave are taken aback, intimidated and a little confused. "But it's all right, because you guys were great." He extends his hand to B.J., who shakes it and then looks over at Dave. The band made $150.

The trip to Aurora seems more like two or three days than 17 hours. By the time we reach Riley's, the show in Savannah feels like a month ago. I drive out of Savannah, all the way back to Spartanburg, S.C., where I turn the wheel over to Dave.

The night before, sitting in a Wendy's parking lot, we had debated whether to drive through Atlanta or back through Knoxville on the way to Aurora. We ultimately decided on Knoxville, though nobody really wanted to see town again until we were done.

As it turns out, though, B.J. busted two drum heads at the Velvet Elvis, so we had to stop at home to pick up his spares. The stop is ugly; we hit Interstate 40 in the middle of Friday morning rush hour, then take back roads to the band's house in northwest Knoxville.

While the band guys take quick showers and B.J. calls his girlfriend (Alex worries that we'll never get back on the road), I eat a bowl of cereal. My car is in the driveway. My keys are in my pocket. I'm just sleepy enough and grumpy enough to wonder why the hell they didn't simply pick me up on the way back through Knoxville. Dave and I sleep in the back of the van all the way to Indianapolis. We had figured on seven or eight hours from Knoxville; it takes 10 to reach Aurora. There's a moment when we stop at a rest area, and it feels like we'll never make it. All of us are grouchy and irritated.

"I'm almost ready to just cancel this show," Alex says.

We all light up at this; B.J. and Dave seem more than willing to get a room near Carbondale and rest for the next night's show.

"But now I want to do it just to say we did it," Alex decides, putting to rest any thoughts of an easy evening in Carbondale. He pats the side of the van. "Everybody said we couldn't do it."

The final show of the trip, at a college bar on the campus of Southern Illinois University, is a fine coda for the weekend. They play in front of a crowd of about 200 people, though many of them are more interested in playing pool than listening to a rock band from Knoxville. The $600 the band earns pushes their total take for the weekend up to almost $900, minus expenses, making the whole tour worthwhile. It's an energetic set, and they dedicate "Chinese Rock" to me.

We spend the night with Kati from the local college radio station. Kati conducted an on-air interview with the band the afternoon before the show and put their self-released CD into rotation. On the way back to Knoxville, we stop at Alex's dad's house in Franklin, Tenn. We play basketball and eat dinner out on the deck, watching the sun drop behind the Cumberland Mountains.

"I've been playing music like this since 1995, and this is the most success I've had so far," Alex had said, driving the van on the freeways outside of Chicago in the early hours of Saturday morning after the show at Riley's. His remarks are tinged with irony, considering that the American Plague has only been a band since February and they're lucky to break even on these brutal weekend jaunts. "I want to just go out and play all these places. I love it. Nobody does it, because it's just ridiculous. But it's what I want to do. I don't want to be on MTV. I just want to be able to pay my rent and eat and play."

November 1, 2001 * Vol. 11, No. 44

© 2001 Metro Pulse

|