|

Comment

on this story

What:

The Prints of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again)

When:

May 25-Sept. 9

Where:

Knoxville Museum of Art

How Much:

$7 adults, $6 seniors, $5 ages 12-17. Free to children under 12 and KMA members. For more information, call 525-6101

|

|

But what does the Pop Art superstar mean 15 years after his death?

by Jesse Fox Mayshark

"Everybody has their own America, and then they have the pieces of a fantasy America that they think is out there but they can't see. When I was little, I never left Pennsylvania, and I used to have fantasies about things that I thought were happening in the Midwest, or down South, or in Texas, that I felt I was missing out on. But you can only live one place at a time. And your own life while it's happening to you never has any atmosphere until it's a memory. So the fantasy corners of America seem atmospheric because you've pieced them together from scenes in movies and music and lines from books. And you live in your dream America that you've custom-made from art and schmaltz and emotions just as much as you live in your real one...It's the movies that have really been running things in America ever since they were invented. They show you what to do, how to do it, when to do it, how to feel about it, and how to look how you feel about it. When they show you how to kiss like James Dean or look like Jane Fonda or win like Rocky, that's great."

—from America, by Andy Warhol

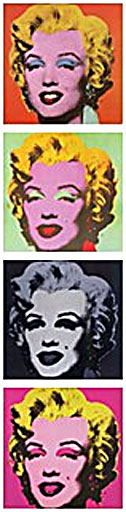

It starts with dollar bills, of course. And S&H green stamps. Then come the soup cans and shoes. Then the celebrities: Liz, Marilyn, Mick, Jane Fonda, Grace Kelly. A little bit of politics, a splash of wiggy abstraction, and a few looming shadows. Cash, commerce, fame, power, and death. Oh, and fluorescent cow wallpaper. This is the life and career of Andy Warhol, or a summary of it anyway, condensed into one exhibit at the Knoxville Museum of Art. The 70 pieces are big and buoyant, poster-sized prints that look exactly like the replicas of them you'll be able to buy in the gift shop.

"When you think about it, department stores are kind of like museums," Warhol said. He would undoubtedly laugh at the recent controversies over gimmicky entertainment-style exhibits at previously high-toned cultural institutions.

The irony is, the Warhol exhibit at KMA is no such thing. Oh sure, the museum hopes it will draw in summer sight-seers by the busload, that the big billboards of a psychedelic blue Marilyn Monroe will entice everyone from beret-bearing art students to nostalgic Baby Boomers to grade-school kids, that people will be lined up 10-deep to contemplate Warhol's replication of a can of Campbell's Hot Dog Bean Soup ("with tender beans and little frankfurter slices").

But even though it's often funny and almost always populist, the art of Andy Warhol is neither a joke nor a sham. His work was a complicated and prescient reflection of his life and era.

"It was a career more nearly like Picasso than anyone else," says Thomas Sokolowski, director of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, the source of the KMA exhibit. "Because like Picasso, he was constantly exploring. You get the notion of a scientist or a mathematician or something: Posit a problem, explore it, and then you're done and you're onto something else."

"When I got my first TV set, I stopped caring so much about having close relationships with other people. I'd been hurt a lot to the degree you can only be hurt if you care a lot. So I guess I did care a lot, in the days before anyone ever heard of 'pop art' or 'underground movies' or 'superstars.'"

—Andy Warhol, from The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again)

Andrew Warhola grew up in Pittsburgh, the son of Czechoslovakian immigrants. Born in 1928, he had an almost stereotypical artist's childhood: sickly and pale, bedridden with recurring bouts of St. Vitus Dance, he spent summers in his bedroom playing with a Charlie McCarthy doll. And he drew pictures. His family was working-class in a radically stratified city, where a handful of wealthy families controlled the industry and everybody else worked for them. Personally, economically and culturally, he was an outsider.

He majored in pictorial design at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University). When he graduated, he moved to New York City.

"Leaving Pittsburgh was important for him, because he was able in a place like New York to do pretty much anything his heart desired," says Sokolowski, who will give a lecture at KMA July 8. "One thing was he almost immediately changed his name to Warhol. It was a modern name. Someone couldn't look at it and say, 'Oh, Warhola. Is that Czechoslovakian?'"

He was successful as a commercial artist, doing drawings for magazines and high-profile advertising campaigns. He also started exhibiting work in galleries. By 1956, he was included in a group show at the Museum of Modern Art. If he ever made any distinction between his "commercial" work and his "art," he eroded it completely by the early 1960s. His famous series of Campbell's Soup prints explicitly challenged assumptions about what art could be and what could be art, and made him internationally famous. Along with comic-book appropriator Roy Lichtenstein and a few others, he was at the forefront of what came to be called "Pop Art."

"Andy Warhol's best-known paintings and prints are usually brightly colored. They have simple, strong shapes that really stand out. Andy often showed things that were a popular part of everyday modern life, like supermarket products and rock stars. The name 'Pop Art' comes from the word 'popular.'"

—Mike Venezia, from Andy Warhol, a children's book in the "Getting to Know the World's Greatest Artists" series

Warhol's embrace of "Pop" arose from several influences. He got his first TV in 1954, and he quickly realized its potential impact. As he put it, "We were seeing the future and we knew it for sure. I saw people walking around in it without knowing it, because they were still thinking in the past, in the references of the past. But all you had to do was know you were in the future, and then that's what put you there."

Timothy W. Hiles, an associate professor of art at the University of Tennessee, says Warhol saw the media as the new defining force in American culture. And just as 19th century landscape painting reflected the literal and symbolic significance of land and the frontier in American life, Warhol's studies of products and celebrities reflected his commodified society.

"[His prints] are very much about how American society can take a person and make them a commodity," Hiles says. "And he did the same thing with himself. He made himself a commodity."

But there was more to it. In the depersonalized media of prints and silk screens, using images stolen from elsewhere, Warhol the outsider found a fit for his introverted, protected self.

"Abstract expressionism was a very subjective type of art, with Jackson Pollock spilling his guts out on the canvas and so forth," Hiles says. "Andy Warhol comes along and says, 'I really can't do that. I need to make objective art.' He tried to be anonymous. The idea was to eliminate the artist's signature from the piece.

"The irony is," Hiles adds, "you'd recognize an Andy Warhol anywhere."

Warhol's studio, the legendary Factory, became a locus of New York society in the '60s and into the '70s. He moved into both music and film, producing the first album by Lou Reed's band the Velvet Underground (generally considered one of the greatest records of the rock era) and experimental movies like Sleep and Blow Job, which showed people doing exactly those things ("reality TV" is a very Warholian idea). He also founded the culture magazine Interview, which is still going.

And he started collecting things, anything. He bought an entire warehouse worth of shoes. He kept 600 boxes of "time capsules" from various points in his life. When he died in 1986, his assorted collections netted $30 million at auction.

"He collected enough until he could understand something," Sokolowski says. "It was almost like creating a museum, a kind of taxonomy.

"For someone who always felt out of it, like he didn't know what was going on...he wanted to say, and then did [say], 'I know what the rules are, and I'm going to tell you what the rules are. I'm going to tell you who's cool and what's neat and who you should desire.' That's what Interview magazine was, really."

"I always wanted to be a comedian. But the nicer I am, the more people think I'm lying."

—Andy Warhol, from America

In the images on display at KMA, you can see several of Warhol's obsessions. However many times you've seen them reproduced in books, the collection of eight Campbell's soup cans takes on new dimensions arrayed in two "shelves" on a gallery wall. Blown-up and viewed for their own sake, the details on the faithfully reproduced labels become absurd: "Stout-hearted soup," "Important! Add whole milk."

Among the most affecting of the pieces in Knoxville is the multiple-panel sequence called Flash, an impressionistic retelling of the Kennedy assassination. There's Kennedy waving, there's a presidential seal with three bullet holes in it, there's Jackie sitting and smiling the moment before the bullet hits, there's Lee Harvey Oswald seconds before being shot. Two of the panels have film director's clipboards superimposed on them—because, as Warhol surmised, this was a kind of show business. Everything was a kind of show business.

"That was really a leitmotif of his art," Sokolowski says. "Everything that we see is seen through a scrim. From that moment [of the JFK assassination] on, every time we see history, history is seen and maybe sometimes even created by television...It was that notion that never again would we see something, no matter how horrible, that it wouldn't be seen through someone else's eyes."

(Warhol was shot himself, in 1968, by disturbed radical feminist Valerie Solanas, founder of the Society for Cutting Up Men (SCUM). Sokolowski says Warhol couldn't help noticing that press reports about his own nearly-fatal shooting were pushed off the front pages the next day by Robert Kennedy's assassination. Whoever was the most famous and the most dead got the most press.)

There's also a mock campaign poster for Richard Nixon. Beneath a photo of the president, painted green and given glowing, ogre-like eyes, is scrawled, "Vote McGovern." "He hated Nixon," notes Nandini Makrandi, KMA's assistant curator. "That's one of the few pieces where it's evident how he felt about something."

"When you see it, you think how incredible it is the way Warhol thought of everything before everyone else. But then, everything else is based on him."

—art critic Matthew Collings on Warhol's film Lonesome Cowboys, from It Hurts: New York Art from Warhol to Now

Warhol doesn't show any danger of fading away, despite his line about everybody being world famous for 15 minutes. A few months ago, Robert de Niro starred in a thriller called 15 Minutes that played with the idea of criminals becoming celebrities (a phenomenon Warhol himself commented on 25 years ago). Just last week, a Warhol print sold at auction at Christie's for $8.4 million.

"I think Andy Warhol will always be considered an essential part of the art of the 20th century," Hiles says. "He's as much a part of the 20th century as Leonardo da Vinci is of the 16th century. His work was avant garde, it was on the cutting edge, and it pushed art in a new direction."

May 24, 2001 * Vol. 11, No. 21

© 2001 Metro Pulse

|