Why Harry Potter doesn't suck

by Dale Bailey

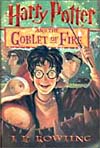

By the time Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire hit the streets last July, I was thoroughly sick of J.K. Rowling and her boy wizard. Sick of hearing how she had conceived the tale while living on the dole. Sick of reading about the gargantuan 3.8 million copy first printing of this fourth volume in a sequence of seven. Sick of the midnight sales, the endless Harry Potter hoopla. I'm a media junkie—the kind of nerd who studies Entertainment Weekly like a Talmudic text—and everywhere I looked, Harry Potter's bespectacled mug grinned back at me.

This kind of thing had happened before. Two months after The Bridges of Madison County debuted, I could have cheerfully brained Robert James Waller with a shovel. By the time The Phantom Menace hit theaters, I wouldn't have cared if Obi Wan had been sucked bodily into the nearest black hole. Nobody likes a sell-out after all—especially a sell-out that comes with a merchandising deal courtesy of Mickey Dee's—and in our secret hearts most of us suspect that if it's popular, it can't be cool.

Sometimes, though, our skepticism leads us astray. No matter how much you treasure that scratched vinyl platter of Boy, U2 didn't really hit their stride until every teeny-bopper in the land was grooving to "Where the Streets Have No Name." Don't get me wrong: I wouldn't advise bingeing on 'NSync's newest disc or whatever maudlin weeper Nicholas Sparks has lately foisted upon us. But I am warning you about getting swept up in the inevitable Harry Potter backlash.

That backlash has begun, and it will only get worse once the trickle of Harry Potter merchandise becomes a torrent and the first film opens in 2001. Nor am I referring to the pious spoilsports who fear Harry might turn their kids into broomstick-riding Satanists. I'm talking about the New York Times Book Review, which last July banished Harry to a new children's bestseller list because he was pushing too many diet books off the discount racks. I'm talking about literary critics such as Harold Bloom, who weighed in on the issue in no less august an institution than The Wall Street Journal. "Can 35 million book buyers be wrong?" Bloom asked on July 7, concluding that Rowling's books will soon join the "vast concourse of inadequate works...[that] cram the dustbins of the ages."

Reading Bloom's dour musings, I couldn't help thinking of Edmund Wilson, the preeminent literary critic of his day, who predicted a similar fate for The Lord of the Rings in 1956. Wilson is lately cramming one of those dustbins himself, but Tolkein's novels still sell millions of copies a year, and when the trailer for a new film adaptation recently went online it became the hottest download in history faster than you can say Pamela Anderson Lee.

I became a believer when I grudgingly picked up Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone to see what all the fuss was about. For the next month, I mainlined Harry Potter like a heroin addict fresh out of methadone. And when the fifth volume comes out next summer, I'll be in line at the stroke of midnight.

From the time Harry climbs aboard the Hogwarts Express, the train that carries him from the realm of normal Muggles like ourselves into a world where mail comes by owl post and jelly beans occasionally taste like boogers, we sense that we're sharing an original vision. In Hogwarts itself, Harry's school of wizardry, Rowling offers a wittily skewed vision of our own world—a world in which diminutive house elves become pawns in a politically correct movement for equal rights and wizard celebrities are skewered by tabloid reporters in The Daily Prophet.

But the real secret of Harry's appeal lies in Harry himself. He is, after all, a very average boy, and despite the epic sweep of his adventures, his concerns are fairly common too: Does his crush Cho Chang return his feelings? Will he pass his final exams? Such are the prosaic anxieties of our own Muggle existences, and watching Harry rise above them to achieve heroism, we can begin to sense the transfiguring possibilities of our own lives and dreams. More than half the appeal of the fairy tales we loved as children is the notion that we too are special, somehow set-apart for greatness, and it is precisely that longing that Rowling taps into so effectively.

If, as I did, you glut yourself on all four books at once, you'll see the formulaic qualities inherent in Harry's annual battle with Voldemort, the evil wizard who destroyed his parents and longs to destroy him as well. But Harry's magic—that transcendental longing for apotheosis—will carry you through.

October 19, 2000 * Vol. 10, No. 42

© 2000 Metro Pulse

|