Comment

on this story

Seven Days

Thursday, Sept. 28

Knox County school and law enforcement officials report increased school attendance, partly thanks to tough truancy policies. Among other things, parents can be sent to jail if their kids don't go to school. What happens if they don't do their homework?

Delta Airlines announces new daily flights from Knoxville to LaGuardia airport in New York City. Problem is, LaGuardia says it's not accepting any new flights during peak hours. Bring a parachute.

Friday, Sept. 29

Mayor Victor Ashe's billboard task force recommends banning all new billboards within city limits. Ashe agrees, saying, "We want to make sure Knoxville is not the billboard capital of the Southeast." Wait a minute—that's kind of catchy.

Knox County students report difficulty in understanding the school board's new dress code, which bans jackets in classrooms, requires shirts to cover midriffs but not pants pockets, and is apparently confusing the heck out of parents, teachers, and principals. There is reportedly education going on somewhere in there, too.

Monday, Oct. 2

The National Parks Conservation Association files a lawsuit accusing TVA's power plants of polluting the air in the Great Smoky Mountains. TVA officials apologetically confess they didn't realize there were any mountains out there "in all that haze."

Tuesday, Oct. 3

City Council approves a new animal shelter, to be run jointly with Knox County. Citizens for Home Rule promptly files a class-action anti-annexation lawsuit on behalf of "innocent kittens and puppies" taken into the city against their will.

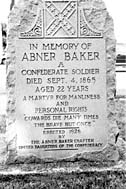

Knoxville Found

What is this? Every week in "Knoxville Found," we'll print the photo of a local curiosity. If you're the first person to correctly identify this oddity, you'll win a special prize plucked from the desk of the editor (keep in mind that the editor hasn't cleaned his desk in five years). E-mail your guesses, or send 'em to "Knoxville Found" c/o Metro Pulse, 505 Market St., Suite 300, Knoxville, TN 37902.

Last Week's Photo:

Who was that mustached man, anyway? Well, he was the friendly greeter on the side of Knox Rail Salvage on Magnolia Avenue (the former Southern Salvage, according to one of our many correct respondents). This week's winner is persistent entrant, downtown architect and k2k chatroom co-founder Buzz Goss. For his effort, he gets a set of lovely bull-and-bear bookends to prop up his investment portfolio.

|

|

A Miami Herald?

Questions linger about Earl Worsham's Florida hotel deal

On the 4th of July in 1999, a Sunday, newspaper readers across Miami woke up to a front-page article in the Miami Herald that traced the rise and fall from grace of an urban revitalization project in the middle of the city's sweltering downtown.

The article detailed how the city, in the early 1980s, had conceived and built the James L. Knight conference center with an adjacent hotel and office tower to bring more people into the moribund business district. The headline called it "a costly dream," and the story quoted several city officials calling the center and hotel "a big cash drain" and "a failure." At the crux of much of the displeasure was the hotel's primary developer—a money man from Knoxville by the name of Earl Worsham.

He is the same Earl Worsham who, with his partner Ron Watkins, proposes to transform downtown Knoxville by building (among other things) a hotel to complement the city's new convention center. While there are many differences between the Miami and Knoxville projects, the Knight Center history is interesting for many reasons, not least of which is that Worsham still claims it as one of his career successes.

Worsham, who is now largely retired, has deferred to Watkins in taking the lead on the Knoxville proposal. But of the two, he is the one with the most experience in the kind of public-private partnerships envisioned by Worsham Watkins International. And the Knight Center, which has been beset with difficulties during its entire 18-year existence, was one of his largest undertakings.

The center has three major components: the conference center itself, including a 5,000-seat auditorium; the adjacent Hyatt Regency, a 650-room hotel; and the NationsBank tower, a skyscraper atop the complex's garage.

"In its development plan, the concept was there would be a relationship between the developer of the hotel, the city of Miami, and the University of Miami," says Christina Abrams, Miami's director of conference, convention and public facilities.

The idea, hatched under the administration of Mayor Maurice Ferre in the late '70s, was that the center would serve as a gateway to North America for industry and commercial interests from Central and South America. (Among other things, the conference center was outfitted with state-of-the-art translation technology.) Under the plan, the university would also book a certain number of conferences per year. The city would build the center, the parking garage and hotel lobby (as is also proposed in the Knoxville deal), with Worsham rounding up investors for the hotel and office tower.

The city took out $60 million in construction bonds for the project. City officials now say they expected the debt to be at least partly covered by revenues from the hotel lease. But because of the terms Worsham negotiated with the city, which are contained in a thick black book he refers to repeatedly during an interview, the hotel developers paid $2.9 million in upfront rent (plus another $1.2 million for part of the infrastructure cost) and nothing else for 12 years.

The lease payment was contingent on a percentage of the hotel's total take, but only if the facility reached $20 million in gross annual revenues. Since it never hit that level between 1982 and 1994, it paid no rent. (It does, however, generate property taxes—approximately $544,000 a year, of which $195,000 goes to the city.) Worsham and Watkins are seeking similar terms in the lease agreement for their proposed Marriott hotel in downtown Knoxville (see this week's Insights column, page 4).

"My opinion is, in the beginning when this deal was structured, it should have been done in such a way that the debt was covered," Abrams says. "And it didn't happen that way."

There's nothing unusual about that. Convention centers are almost always publicly funded and as a rule don't make enough money to pay for themselves. Their benefits are supposed to come from money pumped into the local economy by conventioneers. But Miami officials say Worsham made an especially sweet deal, also securing the food and beverage concessions for the entire center and other auxiliary revenue streams that could have helped defray the city's expenses.

By the time Miami's Knight Center debt is paid off in 2015, the $60 million in bonds will have cost about $195 million. Of that, the city itself will have paid about $150 million, officials say—for a conference center that Bill Talbert, Miami's director of tourism, says is "not at all" a factor in drawing convention-goers. "We have the Miami Beach Convention Center, which is one of the finest convention centers in the country," Talbert says. "Most of the bookings occur at Miami Beach."

Worsham argues that, contrary to current opinion in cash-strapped Miami, the center and hotel were a huge boon to the city. "We put together a project that I am 100 percent confident was the catalyst to $2 billion worth of development in downtown Miami," he says.

Within months of the announcement of the Knight Center, Worsham says, other hotels started going up in the same area. Abrams agrees, noting that three hotels opened within a few blocks—most of which now serve spill-over business from the Miami Beach Convention Center. The NationsBank tower, a 60-story building, is also fully occupied during the day. However, Miami officials say little of that business has translated into lively streets. In the Herald article, University of Miami urban studies Professor Ari Millas was quoted as saying, "Downtown Miami is a national disgrace. It closes up at night."

Worsham says the center wasn't supposed to revitalize the streets. "I don't think the project was designed that way," he says. "It was designed to clean up the city and spur additional investment. I don't know about the street level." The center did include 26,000 square feet of retail space in an enclosed walkway between the hotel and conference center, but the retail failed and the space was turned into an exhibition area. Worsham says the retail component wasn't large enough to generate "critical mass."

The hotel and conference center opened their doors in 1982 to little fanfare—in large part because of nationally publicized race riots that wracked Miami just before the center's debut—and never performed at the anticipated levels. A few years later, Worsham sold half his interest in the hotel to a group of Saudi Arabian investors. Shortly afterward, the lack of revenues caused the hotel to default on a loan payment, which led to bickering between Worsham and his Saudi partners. He eventually sold out all of his stake to the Saudis, at what he says was a comfortable profit. The deal left a bad taste with his one-time partners, however; in a 1987 newspaper account, a spokesman for the Saudi group said, "We'll never do business with Earl again. He took advantage of us, not personally, but of the situation."

In 1994, the hotel changed hands again, reverting back to the Hyatt chain. At that point, Abrams says, the city renegotiated its lease terms to guarantee a minimal annual payment. Since then, the hotel has paid between $650,000 and $750,000 a year to the city. Combined with revenue from the parking garage and office tower, Abrams says, that still leaves the city covering about $2.5 million a year on its Knight Center debt. Some in the current city administration have looked into selling the property, but Abrams says the sale would cover less than a third of the outstanding debt. Instead, the city may build on top of the conference center to create more office and convention space.

Worsham says he hasn't been to Miami for a while, but he still thinks the center and hotel were a landmark in its redevelopment.

"The city, for whatever reason, is displeased with the center," he says. "I didn't design the center, I didn't conceive the center. But the fact of the matter is, [conference] centers are not designed to make money. They're designed to do something else entirely. If they are focusing on the fact that the center is losing money, if they're focusing on the fact that they couldn't sell it for its debt service, that doesn't surprise me a bit. I think it's a non-issue.

"Standing back and looking at it, did the center do what it was supposed to do? I don't know. It wasn't my responsibility. As far as the hotel is concerned, downtown Miami did not have a hotel of the quality level, a four-star hotel, with a flag like Hyatt. So what did it accomplish? It did get its four-star hotel, it did get its flag...Was it a Worsham benefit at the expense of the city? No, it was not."

—Jesse Fox Mayshark

October 5, 2000 * Vol. 10, No. 40

© 2000 Metro Pulse

|