|

Comment

on this story

|

|

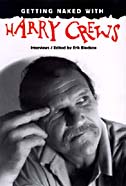

A Knoxville writer's book tries to make sense of Southern Lit bad-ass Harry Crews

by Jesse Fox Mayshark

"Harry Crews."

That's it. No "Hello," no "Harry Crews speaking," just a voice that sounds clenched and very far off saying "Harry Crews."

It's not hard to find his phone number. Just call information in Gainesville, Fla. Getting him to talk to you is more complicated. I'm a reporter in Knoxville, I tell him. I'd like to ask him a few questions about this new book, Getting Naked With Harry Crews. It was edited by a guy here in town, and...

"The interview book?" he says. He sounds a little incredulous.

Uh, yeah.

"I'll tell you what, buddy, I'm a little jammed up right now."

Oh.

"Well, we can do it. Sure, we can do it. It's just a question of when..." He trails off.

I'm going out of town next Thursday, I venture. I could do it anytime between now and then. Or...

"Why don't you call me when you get back?"

Um, okay. Like next month sometime?

"Sure."

Okay, I say. Thanks. End of conversation. The thing is, next month is after my deadline. I know this. I could probably tell him this. Maybe he'd soften up. Maybe we could do the interview right now. But see, this is Harry Crews.

I didn't really know anything about him before reading Getting Naked (University Press of Florida, $24.95), but now I do. I know that he has lived a life of almost unimaginable tragedy, some of it self-imposed. I know that he has fought in bars, wrecked his motorcycles, buried a son, broken his bones, and blitzed himself with drugs and drink so often and so ferociously that people who know him have been predicting his death for 20 years. He's hung out with body builders and circus freaks and Sean Penn. I also know that he writes, that "writing" itself is almost too tame a word for what comes out of him. His books are about people who are maimed and deformed, on the outside or the inside, people who do strange, unaccountable things and either live through them or don't. (Like Herman Mack in Car, who's determined to eat an entire Ford Maverick, from bumper to bumper.) So even from two states away, at the end of hundreds of miles of phone line, Harry Crews is a little scary.

But then, I don't exactly need an interview with Harry Crews. I have a whole book of them. And, fortunately, Erik Bledsoe—who compiled the book—is a lot more approachable. An easy-going, shaggy-headed instructor in the University of Tennessee's English Department, Bledsoe put together Getting Naked With Harry Crews from 25 years' worth of published interviews with the writer. He also wrote the introduction and conducted the final interview in the collection himself. The pieces, which appeared in places ranging from French academic journals to the Detroit-based culture 'zine Motorbooty, collectively serve as an artist's oral history, dominated as they are by Crews' singular, complex, and very Southern voice.

"He has this really rough, tough guy image," Bledsoe says over a cup of coffee at The Golden Roast just off the UT campus. "But the basic concerns are really spiritual—what is our place in the world? I like to compare him to Flannery O'Connor. But the difference is, Flannery O'Connor was a good Catholic girl and had faith; Harry Crews essentially began writing after Time magazine ran the cover story that said 'God is Dead.' And so what do you do when you've been raised in basically a religious society, and yet you don't have that faith—but you want it?"

Crews, who's been on faculty for years at the University of Florida, grew up in the hard world of rural southern Georgia and the factory towns of northern Florida. He detailed his upbringing in the 1978 memoir A Childhood, his one major work of non-fiction. It opens with his father catching gonorrhea from a Seminole prostitute and continues through domestic traumas including death, drunken beatings, and—for Crews himself—nearly fatal illnesses and accidents. And yet the tone is neither bitter nor sentimental. Here's his oddly graceful description of falling (during a game of pop-the-whip) into a cauldron of scalding water that was being used to boil freshly slaughtered hogs:

"I remember everything about it as clearly as I remember anything that has ever happened to me, except the screaming. Curiously, I cannot remember the screaming. They say I screamed all the way to town, but I cannot remember it. ... Then hands were on me, taking off my clothes, and the pain turned into something words cannot touch, or at least my words cannot touch. There is no way for me to talk about it, because when my shirt was taken off, my back came off with it."

Crews started publishing in 1968, with The Gospel Singer, and has since produced 17 books, mostly novels along with some collections of essays and articles for magazines like Playboy and Esquire. His work is generally well-reviewed, and his following, at least among devotees of modern Southern literature, is considerable. But he's also had plenty of detractors over the years, who have accused him of grotesquerie and indulgent violence. For example, while both the New Yorker and New York Times praised his 1987 novel All We Need of Hell, a USA Today critic called it "a repellent little book," and added, "Shame on you, Harry Crews."

Bledsoe thinks Crews, who is now 65, is due for broader recognition.

"I think that's changing even as we speak," he says. "And I think it's changing because of the newer generation of writers. Folks like Larry Brown who are getting lots of attention repeatedly refer back to Harry Crews as being a kind of literary forefather. ... I think he's kind of helped to map out certain territories."

Of course, what makes Getting Naked great reading is the character of Crews himself. Always articulate, often funny, and sometimes just plain pissed off, he takes all comers, from post-modernist writers (he can't stand them) to his "peers" in the English Department at the university ("I ain't got no peers in Gainesville...They ain't been around no blocks. They ain't seen blood, and all their bones are intact"). He's an unapologetic advocate of his own work, and wonders aloud when he'll make a mass breakthrough (or, as he puts it, "write a book that's just going to knock everybody's dick in the dirt"). But he also speaks reverently of a host of writers: Flannery O'Connor, Graham Greene, Truman Capote, James Agee. In some of the interviews, he is either drinking or drunk. In others, he's making one of many efforts to clean up. But in all of them, he's trying to make sense of the world.

"Who would be evil?" Crews asks at one point, responding to a question about morality. "Why would you be evil? Why would you starve the Georgians in Russia? Why would you shovel people into furnaces? You can't think about that. And yet, my God, my God...It is the thing in us that keeps us fascinated with ourselves. It fascinates us with ourselves much more, the animal in us, the flesh-tearing, brutal animal in us, fascinates us much more than the kissing, licking sweetheart who sends valentines, who cares enough to send the very best."

Much of the book focuses on the process of writing. The title comes from one of Crews' many discourses on the subject: "If you're gonna write, for God in heaven's sake try to get naked. Try to write the truth. Try to get underneath all the sham, all the excuses, all the lies that you've been told."

Talking to writers about writing is, like any effort to understand the mechanics of art, a dicey proposition. But in compiling Getting Naked, Bledsoe says he was trying to get closer to the elusive drive that can propel someone from the least likely places to a life in front of a typewriter.

"How is it that Harry Crews, who grew up the son of a share-cropper in Bacon County, Georgia—and I've been to Bacon County, Georgia, there ain't much there...and yet out of that emerges a writer," Bledsoe says. "And that fascinates me...It's not surprising that Hemingway's kids have written books. But when you come from a family that never reads?

"The reason I read biographies, the reason I read interviews, is to try to understand the whole creative process," he continues. "What makes some people have that and some people not, what makes some people Picassos, and why is it that I can't even paint a sunset?"

Bledsoe—who says the writer was magnanimous and thoughtful during his own interview—says he thinks Crews is pleased the collection of his scattershot musings and other people's musings about him is out there. Whether he's actually read it all or not is another question. In one of the interviews, Crews says, "I never read any reviews or stuff, and I certainly don't read interviews because I always sound like such a fool and I get stuff wrong. When it's wrong, I say to myself, 'I couldn't possibly have said that.'"

Meanwhile, Crews is still writing, publishing books every couple of years. In A Childhood, he talks about how, as a boy, he would pore through the Sears Roebuck catalog and make up stories about all the perfect people he saw pictured there, about the betrayals and tragedies that must be lurking beneath their facades. In one of the interviews in Getting Naked, he says he's been doing the same thing ever since:

"How many marriages have you known that the man and the woman would come into parties, they were smiling to one another? They were holding hands, they were arriving in the same car. They, as they say, 'maintained appearances.' And then one day you hear from a friend, 'Did you know that Pete and Sally's gettin' a divorce?' And you think, 'No man! Wait a minute. I didn't know that. No, you gotta be wrong. Pete and Sally came to my house and they were all huggy-bear, kissy-mouth and that kind of bullshit thing.' But no. Underneath, the worms were crawling. They're eating eyeballs...All very sad. All very tragic. And all very ugly enough to make a man almost murderously angry. But that's the nature of the world. I don't know about you, but the only world I know is the one I see."

July 13, 2000 * Vol. 10, No. 28

© 2000 Metro Pulse

|