|

Comment

on this story

|

|

Surber and Terry make the viewer aware of refined sensibilities

by Heather Joyner

Many great books would not exist had their authors dismissed what could be done with the same old language or familiar themes of selfhood, love, and loss. Conversely, one might say that art has often suffered when its primary aim has been to blaze a new trail with every brush stroke, line, or thrust of a chisel. When I catch myself thinking there's nowhere for painting to go at this point in time, I'm forced to ask what intentions aside from innovation the medium serves. Whether or not the "new" yields meaningful insight into what's come before, it can seduce or repulse (or do both simultaneously) simply because it is different. Either way, it gets our attention. As part of a culture in which relevance is sometimes confused with that which manages to smack us in the face, we're set up to miss a lot. We've become restless and have forgotten how to simply look at things. And "simply looking" affords much pleasure for those visiting the Hanson Gallery within the coming weeks.

What, then, might the intentions of Robin Surber and Christopher Terry be? As highly accomplished Knoxville artists who have exhibited together at the Hanson Gallery before, both Surber and Terry have roots extending into the past; neither has created work that could be called especially novel. Yet their show A Room For Two, like James Ivory's film A Room With A View, provides a glimpse into very specific and refined sensibilities that perhaps make us more aware of our own. Whereas Surber is a painter of recognizable subject matter, Terry is more of an "abstract imagist" (in the vein of color-field artists such as Mark Rothko and Jules Olitski). Each poses the question of what is content versus subject matter. Paul Klee remarked that "...art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible." That said, the artist's perception made visible could be considered a work's content/meaning whether we're looking at objective or nonobjective painting. It's been stated that the world "was offered up to Henri Matisse to be shaped by the grace of art," and Matisse expert Gerard Durozoi has written, "What importance would painting have if it could not represent, in its individual way, things that speech cannot express?" In A Room For Two, each artist's answers are very different but equally stimulating...we get to have our abstract cake and eat it, too.

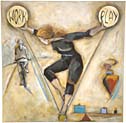

Surber's work runs the gamut from canvases like the highly figurative "Balance," showing an acrobatic woman juggling spheres labeled "work" and "play," to smaller images in which a sleeping cat or landscapes are superimposed on cups and saucers. Sounds odd, but such juxtapositions seem to work. Personally, I'd rather that "Balance" did not rely so much on words to convey its message. I also find some of Surber's highly decorative frames (be them studded with metal or adorned with tassels) a bit distracting—essentially gilding the lily. But all in all, her paintings are extremely captivating via their sensuous surfaces and handling, decisive composition, and unusual use of color. It seems no piece could be any more or less than what it is.

A former ceramicist who augments her fine art-generated income by creating murals for establishments like Chesapeake's and the McGhee Tyson Airport, Surber paints every day. She also turns to members of her "Sisters' Keepers" group (which includes Debby Hagar, Bev Howard, and Susan Wood-Reider) for criticism and encouragement. Surber says she knows when a particular painting is complete. "I get a taste in my mouth. Literally. I kind of smack my lips and I know that that's it." Returning to Matisse, her "Quiet Visit" (with its fish bowl perched on a Victorian-looking table) is especially reminiscent of the master's goldfish images from the 1910s. Greens and pale bottle blues surround a bowl that, like Matisse's, "...symbolizes the liberty of color in relation to the material nature of common objects...at the same time [underlining] the equal value of surface and representation" (Durozoi). Surber's "Red Garden Gloves" is another subtle achievement.

Like Surber, Terry displays approximately 15 pieces, also completed since January. He strives to achieve "a certain softness" and says, "To me, abstraction should make sense of chaos." If impasto and brush strokes emphasize the painter's touch, the apparent absence of the artist's hand in Terry's smooth canvases lends them an ethereal quality. Applying acrylics to printmaking paper as well as canvas, Terry achieves a remarkable richness of color. He begins by wetting the paper completely and prefers to go from dark to light, "...getting as much down in the first few hours as possible." Pieces like "Urban Renewal" and "Visiting Vanessa Bell" (named for a woman who, like E. M. Forster and Bell's sister Virginia Woolf, was part of London's Bloomsbury Group in the early 20th Century) are meditative in feeling without being dull. A golden satin varnish brings out Terry's colors and intensifies their luminosity. Originally from the Tri-cities, Terry attended the University of Miami and has studied with artists in Wisconsin and Arizona in addition to working with Anton Weiss in Nashville.

Both artists will be present at the Hanson Gallery during tomorrow evening's reception and offer an enjoyable way to spend a Friday evening in May.

May 4, 2000 * Vol. 10, No. 18

© 2000 Metro Pulse

|