|

Comment

on this story

What:

Moving Pictures About Fort Sanders

Where:

UT's Art & Architecture Building (Room 109), and at the Laurel Theater

When:

UT Screening on Mon., April 10. Laurel Screening on Thurs., April 13. Both are at 8 p.m. with free admission.

|

|

A-1/LAB presents films and videos about the Fort Sanders community

by Heather Joyner

One recent and drizzly Thursday evening, I met with UT senior Christopher Lowe on the top floor of the Art and Architecture Building on Volunteer Boulevard. Majoring in Media Arts, Lowe looks like a less husky version of comedian Drew Carey, and like Carey, his appearance is deceptive. Beneath an all-American, bespectacled, and (dare I say?) ordinary veneer lurks what seems a rather quirky personality; someone who refers to himself as "a thorn in the side of authority." I spoke to the young filmmaker and performance artist as others milled about a cantilevered office area converted into a film projection and editing facility—a remarkably small space serving what Lowe says is "a core of about 12 to 15 students who are really serious about film and can compete with students anywhere." I also saw his almost-finished, 6-minute piece titled Highland Avenue: Crossing 11th Street, 12th Street, 13th Street, 14th Street, 15th Street...23rd Street, one of four Fort Sanders-related shorts that will be screened beginning April 10. The film made me especially curious about the other films being presented (which I unfortunately could not view before this column's deadline).

The project called The Fort began when former Arts Council member John Winemiller discussed an idea he had with Norman Magden, head of UT's Art Department. Through his work for the Arts Council, Winemiller became involved with the now 6-year-old non-profit intermedia arts cooperative known as "A-1/LAB." When he learned that funding could be sought from the East Tennessee Foundation for a community-based filmmaking effort, he "wondered how A-1 could tap into that and felt that Fort Sanders would be a timely and important topic...perfect for an art project."

In his proposal to the East Tennessee Foundation, recipient of a five-year, $500,000 "Community Partnerships for Cultural Participation" grant from the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest fund (with matching contributions totaling $1 million), Winemiller detailed the plan that would produce next week's film and video screenings. He wrote, "While Fort Sanders has been evolving for decades, the neighborhood is at a critical juncture... The Fort focuses on how the diverse population of seniors, young professionals, working families, and students is responding to development plans that are sure to impact the design and character of the area... [a place] as dynamic and colorful now as it was when portrayed by James Agee. The Fort will ask what 'community identity' means, and why the residents of Knoxville's most famous neighborhood value it and fight to preserve it." Co-sponsoring the project are the UT Art Department and the Historic Fort Sanders Neighborhood Association.

This past autumn, artists submitted examples of their work alongside written statements in hopes of taking part in The Fort. From the entrants, four were chosen by Magden and award-winning filmmaker/UT art professor Kevin Everson to receive funding for their films and videos.

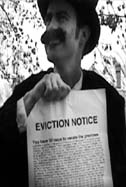

Like the neighborhood that is their focus, those selected represent a range of ages and experiences. In addition to Lowe, there's Laurel High School student Frank Ragsdale and UT Communications School alumna Cathy Riviere (with perhaps the most "professional" background of the bunch, having produced an episode of The Heartland Series). Riviere will present her piece Once A Battlefield, Always A Battlefield. Also chosen was community activist James Henry, who will show his 30-minute video Giving Up The Ghost. The film is made up of a narrative segment and two fictitious story lines that include a mad monk and a Snidely Whiplash-like landlord tying up Henry's version of Little Nell. Henry, who has lived in six properties that have been demolished within a 10-year period—and has been evicted from three for that reason—jokingly says, "It's payback time." He calls himself a refugee from the Fort Sanders "student ghetto" and remarks, "There's a lot of anger on my part with it all, but I'm trying to make it funny."

Interestingly enough, the unveiling of participants' efforts and related remarks from both artists and community members will coincide with a Metropolitan Planning Commission meeting addressing Fort Sanders' future, scheduled for 1:30 p.m., April 13 (in the Main Assembly Room of the City County Building). Metro Pulse writer and Knox Heritage board member Matt Edens asserts that the meeting comes at an important point in time, saying, "The Fort Sanders Forum has already passed the MPC Plan, the key point of which is establishing a conservation district and a design review process. [That means that] demolition permits would be subject to approval by the Historic Zoning Commission. Public support really counts right now because the decision ultimately rests at the feet of the City Council." Although each of the above artists was instructed to create an artistic rather than a documentary piece, their work could be considered part of this ongoing dialogue about the future of what we fondly refer to as the Fort.

A-1/LAB has stated, "We [wish to appeal] to residents of Knoxville's other historic neighborhoods facing similar development challenges...[and] we hope that various civic leaders and decision-makers will join us at one or more of the screenings of The Fort... through this artistic process, we hope that Fort Sanders will learn something about itself." As local musician, writer, and all-around renaissance man R. B. Morris puts it in his poem "Return," "Pretending to have a plan, I say // First we must rearrange all these buildings // and flush the river clean // Reshape the clouds // and put back the neighborhood // Then we must sleep // When we wake // We will walk down these streets // We will eat and drink // We will talk to those we meet // and see who they are // We will return to here."

Watching Lowe's 16-mm silent film, I might have read some things into it that were not necessarily intentional. His long walk along Highland with an inverted camera (held upside down so that the film could be run backwards through the projector) is captured at 12 frames per second, lending it a slightly speeded-up energy and jauntiness.

"The Fort has a communal feeling—it's a place where everyone knows someone on almost every block," says Lowe. "I see straight narrative [as being] dead and old...I thought it would be more interesting to just go out into the neighborhood. Every college town has a place like this; it's universal. My friends get to step back and see their neighborhood projected. It's a different way of looking at things."

Lowe's piece is dominated by a straight-on view of sidewalk stretching into the distance, punctuated by the movement of passing cars. That it's so full of concrete and pavement falling away backwards suggests transience and loss—what's before us is rapidly being pulled away. That it doesn't allow us to take in what's to our left or right creates a sensation of being routed, blinded. In a way, it speaks to many people's fears of losing Fort Sanders' history. And like moments only represented on film, what's gone is gone forever.

April 6, 2000 * Vol. 10, No. 14

© 2000 Metro Pulse

|