|

Comment

on this story

|

|

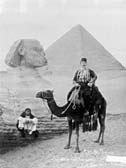

UT's McClung Museum documents a photographic and archaeological adventure

by Heather Joyner

Egypt, 1857: In 115-degree heat, British photographer Francis Frith labors away in a stuffy, fume-filled tent. Unlike those who drift leisurely in "dahabiyehs"—vessels occasionally equipped with photo labs as well as sleeping cabins—Frith is no-frills. Whatever the conditions, his exposed collodion-coated glass plates require masterful handling while still wet with a chemical that steamship lines refuse to transport (since collodion has an explosive active ingredient often used for a specific type of gunpowder). Thus, Frith's task is not only to produce prints in adverse circumstances, but to do so employing a smuggled-in substance requiring guncotton and hen's eggs to be processed. No wonder one Egyptian khedive, a viceroy of the Turkish sultan, proclaimed it the work of the Devil when he first beheld a photograph.

The Koranic prohibition against realistic images alone would make photography and its practice by native Muslims evil. Add to that the new medium's portrayal of 19th century Europeans as superior civilizers and you had a technology to be reckoned with. The very expression "taking pictures" became scary, as demonstrated by an Abyssinian nobleman mentioned in Nicolas Monti's Africa Then. He said of photographer Edoardo Ximenes, "This man has too much in his camera and I think it's enough. Does this man want to take away the whole country?"

Long before Napoleon, people had been taking away the treasures of Egypt's past, in one form or another. The title of the McClung Museum's newest exhibit (featuring 80 photographs as well as 50-plus excavated objects on loan from museums around the country) includes the word "scoundrel" for a reason. Like the American gold rush, which occurred a decade after the unveiling of Daguerre's invention of photography at the French Academy of Science, African colonialism was fueled by greed. Writes Monti, "...the colonial enterprise became an unforgivably absurd adventure, which allowed fringe sectors of bourgeois society to explode into the worst kinds of misdeeds, sooner or later to meet with their well-deserved destruction in God-forsaken countries with unpronounceable names, among peoples with whom physical and moral violence seemed to be the only possible form of intercourse." Interestingly enough for us, the advent of photography just happened to coincide with this era of heavy-handed expansion.

The Egypt that French archaeologist Auguste Mariette found in 1850, with its oft-looted tombs and abused antiquities, infuriated him to the point that he became the first "guardian" of Egyptian monuments. According to Egypt: Land of the Pharaohs, "As Mariette and his successors all too quickly learned, there was no easy way to stop the despoiling that had been going on since the time of the pharaohs themselves...an unholy lot, the tomb robbers showed little respect for the dead. One group thought nothing of turning the mummies of children into torches with which to light up their work...in a search for gold, the robbers often ripped off [mummies'] heads, arms, and hands and tossed them aside." In addition to providing examples of scarabs that were buried in dung mounds then dug up to appear more ancient, the McClung show includes an image of a sphinx with graffiti scratched into its outstretched legs.

Mariette, best known for his discovery of the underground Apis Galleries of Memphis and coffins containing embalmed sacred bulls, was no saint in the eyes of later archaeologists, however. Englishman Flinders Petrie denounced Mariette's use of dynamite for excavation and his sloppy or nonexistent record-keeping. Alongside American George Reisner, Petrie represents the increasingly meticulous and scientific methodology of archaeological investigation during the latter part of the 1800s, extending into the 20th century. Throughout 45 years of digging, Petrie was equally dedicated to diverting onlookers—choosing as he did to strip down to red underpants on particularly hot days.

Curated by Elaine Evans, Scholars, Scoundrels, and the Sphinx inhabits a small space, but is chock full of items and information. Perhaps so much so that a few return visits are in order; the two-hour parking permit granted museum-goers does not allow sufficient time to take it all in. After all, we're seeing how one time period (roughly 1850-1930) perceived many other periods. It helps that the outer walls of the exhibit focus on 35 sites and their artifacts and have clever maps showing each site's location along the Nile, whereas an interior partition addresses the more recent past. Wall-mounted and recessed cases abound, containing everything from exquisite jasper and carnelian jewelry and the "Head from a Ba Statue" (bearing a remarkable resemblance to actress Shelley Duvall) to a Victorian Era, bead-handled "fly whisk" and exotic postcards showing fashionable tourist hotels. There's even a Thomas Cook and Son "circular note" circa 1911—an early traveler's check for the security-minded. Written descriptions are thorough and often poetic, such as one describing the pyramids of Gizeh as "...weather beaten, punctured by treasure seekers and weapons, and in part hidden by the constancy of desert sands." This was, as older photographs reveal, a time when monuments now entirely familiar were still half-buried.

All in all, Scholars, Scoundrels, and the Sphinx is a demanding but rewarding show intended for a mature audience (children are better off let loose in the adjoining exhibit titled Ancient Egypt: the Eternal Voice). A series of free lectures begins at 2 p.m. this Sunday, March 12, with The Brooklyn Museum's Dr. Richard Fazzini's "Egyptomania in American Architecture." Also taking place in the museum auditorium are lectures scheduled for April 9 and May 7. Ah, the abundance of Spring.

March 9, 2000 * Vol. 10, No. 10

© 2000 Metro Pulse

|