|

Comment

on this story

|

|

Yee-Haw's "new church of typography" keeps the artform of letterpress printing alive.

by Coury Turczyn

The first thing that strikes you upon entering the butcher-paper-masked headquarters of Yee-Haw Industrial Letterpress is the smell of ink. It permeates the air like a comforting memory of times gone by, warm and moist—completely unlike the metallic tang of expended toner that attacks your nose at the ever-pervasive Kinko's. At this print shop, the machines don't dryly huff or cast scanner beams—they clank and kerchunk and roll bright hues of ink onto thick sheets of chipboard and fibrous paper. It's a place where people really work hard, and look like they love doing it.

Things are slightly disorganized right now, not quite ready for public viewing. Boxes are jammed in corners, the front counter still doesn't have its top glass, a giant costume pig head sits cockeyed, smiling and waiting for someone to put it on. But when Yee-Haw opens its glass doors at 413 S. Gay Street next month—after a year of preparation—visitors will be entering a dimension where age-old printing techniques and pop folk art have been fused to form a one-of-a-kind enterprise. Part museum, part graphic design business, part gallery, Yee-Haw is a shrine to the nearly dead artform of letterpress printing—that Gutenberg-approved method of pressing paper against inked plates of text to create a printed page. Sent to oblivion by modern offset printing, letterpress is now usually considered either a quaint curiosity or, worse, an antiquated technology not worth saving. But not at Yee-Haw.

Co-owner Kevin Bradley, goateed and slightly scraggly like any good artist, pulls open a drawer from one of the century-plus-old type cabinets that line Yee-Haw's storefront space. He plucks out a large wood block inscribed with a fanciful "A."

"This is a circus font that came out of Memphis," he says, thumbing the still-sharp edges with appreciation. "They did it out of wood because it was lighter and more manageable, plus it held up very well—this stuff goes back to the early 1800s. We got this out of a barn in New York state."

"Covered in porcupine turds," adds Julie Belcher, Yee-Haw's other owner and designer in residence. Together, the thirtysomething duo has scoured several states for long-unused equipment hidden in warehouses, basements, and barns. They've become letterpress archeologists, uncovering musty warrens stocked with type cabinets and paper cutters and presses. The circus type from Memphis came by way of an old collector in New York state—he and his father had followed the Mississippi River buying up type in the '50s. (In the 19th century, the river was the best way to move heavy equipment, thus many letterpresses were located near rivers.) Stashed in his dairy barn for decades, and being attacked by porcupines, the type was rescued by the Yee-Hawers when the owner realized they'd be using it for its intended purpose rather than selling it off at $20 a pop as flea market curios.

Through similar deals with former pressmen and retired dealers, the Yee-Haw HQ is now stuffed with millions of pieces of wood and lead type, several Vandercook presses, a giant paper cutter, and a newly acquired '50s-era Heidelberg press that looks like a multi-tentacled mechanical beast. ("The Cadillac of letterpress!" Bradley declares with pride.) Most of these deals were less business transactions than they were a passing of the torch.

"We really strike a good connection because we take samples of what we're doing and show them we're carving blocks, printing wood type, doing it by hand—and I think they really dig that quite a bit," says Bradley. "We pretty much have working relationships with all the people we've bought equipment from. They just appreciate the fact that we're still using it."

The idea for the Yee-Haw enterprise was hatched three years ago near the ovens of Peggy Hambright's Mag-Pies, where Bradley and Belcher met. UT art school grad Bradley had returned to Knoxville in 1996 after spending the previous two years working at Nashville's Hatch Show Print, one of the country's few traditional letterpress shops still in business. Likewise, Belcher (a former Whittle Communications designer) had come back to Knoxville after spending several years in New York as a grad student at the School of Liberal Arts and a full-time freelancer for Seventeen magazine and Blue Note Records. Both were searching for something to do with themselves, stuck in career limbo as they helped out at Mag-Pies.

"I didn't want to get a graphic design job because I knew I'd be sit-

ting at a Macintosh and doing brochures or whatever you have to do," says Bradley. "I never liked sitting in front of the Mac because I felt it was stealing my soul in a lot of ways. So I discovered alternative ways of getting type on paper, and letterpress seemed to me to be the way to go with it."

Although Belcher wasn't very familiar with letterpress, Bradley's knowledge and enthusiasm won her over when he suggested they start their own business. "One of the things that really attracted me was these are all elements I already knew about—using design to combine typography, illustration, photography," she says. "It's just a different way of doing it. I never used a computer in college, so this is just like full circle."

So how do you start a new business using outdated, centuries-old technology? Belcher and Bradley began with the phone book, calling every printer in town and asking if they had any letterpress equipment to sell. They began hearing horror stories of how in the '60s, when letterpress became completely obsolete, wood type collections were bought out for a few hundred bucks—and used for kindling. But with the help of inquiring friends in other states, the pair started tapping into the letterpress underground.

First, there was Nelson Nidiffer in Huntington, W. Va., a septuagenarian dealer who used to buy out print shops of all kinds and still had a 30,000-square foot warehouse full of every piece of press equipment imaginable. ("He let us run roughshod in there for about a week, and we were just picking out stuff we wanted, like kids in a candy store.") There was the guy in Barberville, Ky., whose father had started the newspaper there in the '30s—he had type cabinets stored in an old barn, the drawers swelled shut with age. ("We had to pry them open with crowbars.") Right here in town, there was Holland Ingram down at Stubley-Knox Litho Co., who had a completely intact collection of beautiful type. ("It was amazing—it was all pointed in the same direction.") The Heidelberg was acquired from a family-run printer in Rochester, N.Y., after being used for three generations. ("The son was forced to work on it as a kid, so he hated it—just wanted to get rid of it.")

"It's really fun to go 20 miles down a dirt road to this man's house, and then go a few more miles down the road to this barn, and there's like four cabinets of type in there," says Belcher. "We just sit there all day going through the drawers, just looking to see what there is, just getting excited because you always find something that you're thinkin' 'man!'"

Once the partners had acquired some of this equipment, they needed a place to put it—and found they really couldn't afford to buy a space. Thus, they hauled their stuff to Belcher's family barn in Corbin, Ky., where they opened shop two years ago. Working out of those unheated, cramped quarters, they launched Yee-Haw by creating posters from some of Bradley's quirky folk art paintings and mailing them out to art directors and record labels. They weren't sure how much response the mailings would get—Corbin isn't known for its design studios—but the calls started coming in and clients lined up.

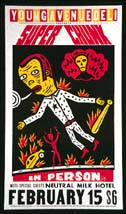

Yee-Haw's work has ranged from creating typography for Southwest Airlines (for a campaign they still haven't seen) to designing posters for the Kentucky Derby. Some of the more glamorous gigs have involved music tour merchandise—T-shirts, posters, and hats for stars like Lucinda Williams, Mary Chapin Carpenter, and Southern Culture on the Skids (who also requested funeral fans). Right now, they're working on a poster for the Dave Brubeck Quartet based on an old Paul Klee painting. That job will necessitate the carving of five different blocks (one for each color) by hand; each poster will then require five passes through the printer. Top speed on the Vandercook is about 16 prints a minute. Altogether, it'll take about a week to complete the Brubeck job.

"You've got to be a bulldog," says Bradley. "It's all hand-done, hand-cranked, hand-printed. So it's really labor-intensive work." Once printed and dried, a Yee-Haw poster has a tactile sense of the work involved—the Vandercooks apply 2,400 pounds of pressure onto the paper, which leaves behind not only inked letters but also indentations. You can feel the words and graphics on the page.

But it isn't just antique fonts and old-timey printing methods that has won Yee-Haw its clients—it's also the artwork created by Bradley, Belcher, and contributors such as Timothy Winkler and Jennifer Jessee. Yee-Haw posters radiate with cartoon aliens, devils, and pin-up girls, surrounded by mystical beat incantations, like this one for Lucinda Williams: "She sings like an angel * From Lake Charles Louisiana * With a broke heart-fact * Raised on polk-salad and poetry." In the world of graphic design, it's safe to say they're truly unique—singular enough to land Yee-Haw on the cover of this month's Print magazine, a leading graphic design publication.

"What we've really tried to do is hand-carve illustrations and typography using the letterpress, and create a new letterpress piece with it," says Bradley. "And it's tough because sometimes you feel like it is art—it's a limited edition, there's only 200 of these in the world, and we've hand-carved them and hand-printed them. And then on the other hand, you're thinking nobody gives a damn. It's something on paper and it's gone out there. You fight between that, but you just have to believe in it—you just have to love it to do it, and it all washes out."

After a year of constant work and unexpected success, though, Bradley and Belcher realized in '98 that they had to find a new, larger space—preferably one with climate control and a retail storefront. After investigating the real estate in Chapel Hill, Asheville, and Nashville, they opted for Knoxville "because there were all these buildings down here that were empty," says Belcher. "But it was a lot harder to actually get one than we thought it was going to be—it took a lot longer. But we wanted to be downtown."

They finally chose the Gay Street location after initially trying to join the city's grand plans for Market Square, sending in a proposal and letters of recommendation. Not much happened. "I wish that had worked out, but it was just taking forever," says Belcher, "and we were ready to go, to start renovation, and to get down here. We'd probably still be waiting." (Over a year later, the city still hasn't followed through on its grandly announced "Digital Crossing" plans.) The partners ended up buying the former home of Downtown Wigs (and before that, Baker Shoes), and sunk far more money than they expected in bringing the aged building up to code—new wiring, plumbing, accessible bathrooms, fire-wall stairs. Although they both sum up the year-long experience as "hell, hell, hell," the partners say they're happy with their new home.

"Even though Gay Street's almost deserted and looks like hell, it still feels great to walk out in front of the building and say, 'Wow, we're downtown,'" says Bradley. "It feels good. Of course, we have a history here, we both went to school here, and have lots of friends here—this is where it started in most every way for both of us."

Now that most of the equipment is in place, the Yee-Haw crew (including interns Kate and Kyle) will start up production on a backlog of orders. In the near future, Belcher and Bradley also hope to open up other floors in the facility, perhaps putting a gallery upstairs and papermaking, darkroom, and metal-working facilities in the basement. With any luck, it'll be the kind of business that becomes a regional institution, perhaps more famous and beneficial to the community than any number of imaginary digital crossings.

|